The Founding Physicians

As Johns Hopkins' most famous medical school professors, they sat in the London studio of famed painter Johns Singer Sargent in 1905 for a portrait that now hangs in the Welch Medical Library. (Lore has it that much of Halsted's figure was painted in disappearing pigment, so disgusted was Sargent with Halsted's strident objection to having blue shadows painted under his eyes. Halsted does, in fact, appear a bit fuzzier than his colleagues, but curators and art experts insist that is only because Sargent painted him farther in the background, and used a thinner wash, for perspective.)

As Johns Hopkins' most famous medical school professors, they sat in the London studio of famed painter Johns Singer Sargent in 1905 for a portrait that now hangs in the Welch Medical Library. (Lore has it that much of Halsted's figure was painted in disappearing pigment, so disgusted was Sargent with Halsted's strident objection to having blue shadows painted under his eyes. Halsted does, in fact, appear a bit fuzzier than his colleagues, but curators and art experts insist that is only because Sargent painted him farther in the background, and used a thinner wash, for perspective.)Every one of the "Big Four," as they are known at Johns Hopkins, was a character, a larger-than-life personality.

- Pathologist William Henry Welch was a stout bachelor who loved swimming, carnival rides and five-dessert dinners in Atlantic City.

- Surgeon William Stewart Halsted was known for being tough on students, but his severity masked an almost debilitating shyness.

- Internist William Osler was a known prankster.

- Gynecologist Howard Kelly collected snakes and was an evangelical Christian.

Each of the doctors, in his own way, had a profound and lasting influence on American medical education and research.

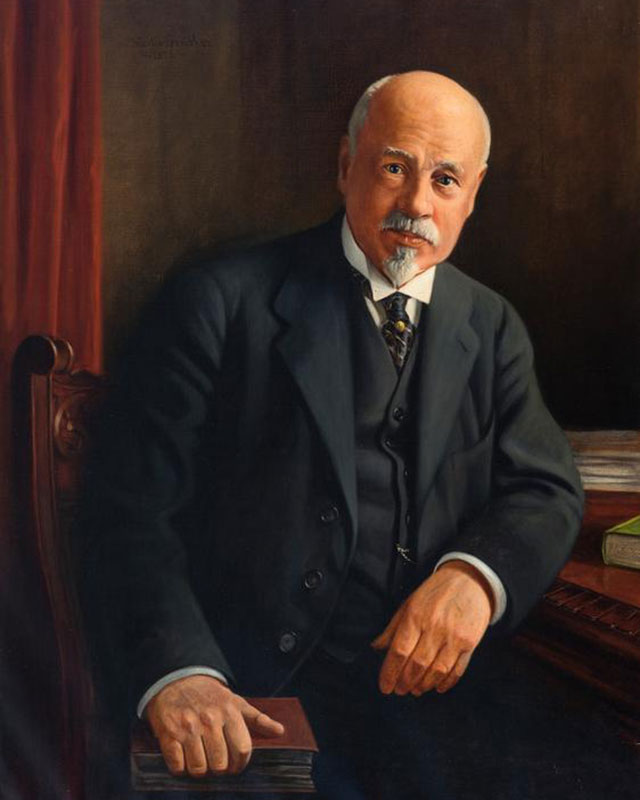

William Henry Welch (1850 – 1934)

Welch joined the faculty first. The last thing he had wanted as a youth was to follow in his country-doctor father's footsteps and take up medicine, since the sight of blood, he said, had always made his knees weak. From age 13, the Connecticut native yearned to teach classics, preferably at Yale, where he eventually went to college.

No job awaited him after graduation, however, and, at a loss for what else to do, he enrolled at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, to the delight of his father, who expected they might practice together when Welch graduated.

Medical education in America during the mid-19th century was relatively undemanding. The New York college was then considered one of the best medical schools in the country, even though its only entrance requirement was that an applicant be able to read and write. Welch, always a diligent student but a lifelong procrastinator, found the program so simple that he didn't have to study for the final, most critical test.

"To tell the truth," he admitted to his sister Emma, "it was the easiest examination I ever entered since leaving boarding school."

Upon graduation, Welch put off joining his father’s medical practice and instead sailed to Germany to train in pathology and bacteriology. He took a dreary teaching job at Bellevue College in New York, where extravagant promises of a hefty research budget and a lab turned out to be $25 and three small rooms furnished with kitchen tables.

As a popular intellectual who enjoyed New York's nightlife with his many friends, Welch made the best of his stay in the city.

He had high hopes that organizers of the proposed Johns Hopkins medical school might recruit him. Earlier, a friend had spoken highly of Welch when talking to the president of the University, Daniel Coit Gilman, and a chance meeting with John Shaw Billings in Leipzig, Germany, when Welch was still in training, seemed to him to have boosted his chances.

The call from Hopkins finally came, complete with assurances of an all-expenses-paid, German-style laboratory, as many research assistants as he needed and freedom from seeing patients unless he cared to see them. Welch, who preferred the pure science of working with cadavers to treating patients, couldn't resist.

By 1886, he had opened his laboratory and was training 16 graduate students — committed research scientists who already had medical degrees and were attracted by Welch's reputation for serious scientific study. His was the first graduate training program for doctors in the country.

Bringing Welch to Hopkins set the precedent of importing top-flight faculty from other parts of the nation, but it also risked causing resentment within the Baltimore medical community. However, Welch's immediate popularity spared him ill will.

His students found him a bit eccentric: An inveterate night owl, he had trouble waking up in the morning and sometimes missed his own lectures. According to one of his proteges, Simon Flexner, Welch completely ignored his students at first, leaving them to their own devices in the laboratory, until on their own each came up with a bit of research that excited him. He always maintained an affable distance that prompted the nickname "Popsy," which they rarely dared to use in his presence.

Welch awed his students with his seeming grasp of any subject. Occasionally he dined with some of his most promising students, where he would talk about art, music, and literature, his students hanging on his every word.

While Welch made some notable research contributions — he discovered the gas bacillus — probably his greatest legacy lies in having trained some of the most eminent scientists of the time. Among them were Walter Reed, James Carroll and Jesse Lazear, who showed that yellow fever is transmitted by mosquitoes. Their finding, considered one of the greatest achievements of modem medical science, led to the virtual eradication of that disease.

Medical schools and institutes across the country vied for Welch's former students and graduate scientists to fill top posts, and Welch served as a sort of national placement officer for academic physicians. It is somewhat ironic that the medical institution committed itself to supplying highly trained researchers to "rival" schools, because it never had room for all its trainees. The result was a revolution in the quality of American medical education and research. Wherever these Hopkins doctors went, they took with them higher standards and expectations.

Welch also played a key role, with University President Gilman and medical institution’s planner John Shaw Billings, in pulling together the original medical school faculty, including Halsted and Osler. In 1916, Welch also founded the nation's first school of public health at Hopkins, and 10 years later he headed Hopkins' Institute of the History of Medicine, now lodged in the medical library that bears his name. He also was instrumental in the founding of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, and served as the first chairman of its board, and of the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

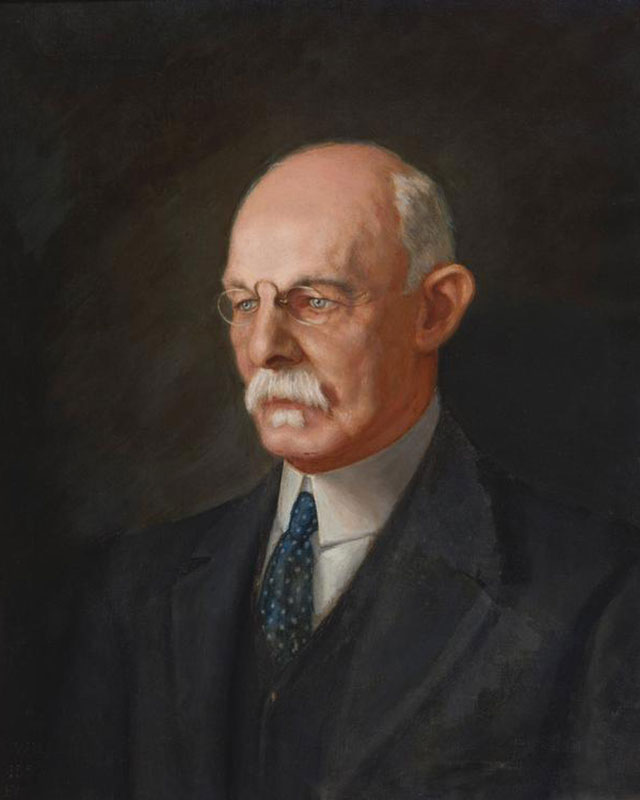

William Stewart Halsted (1852 – 1922)

Halsted came to Hopkins next. He was an almost excruciatingly slow, meticulous surgeon known for his gentle handling of tissue at a time when rapid, vigorous cutting, without thought of germs, was more common.

The aristocratic Halsted fought a lifelong battle against drug addiction after a bout of self-experimentation with cocaine’s newfound anesthetic properties. In practice in New York, Halsted had discovered that an injection into a major nerve trunk could numb a whole limb or block the spinal cord. While his experiments led to modern dental anesthesia, his addiction landed him in a New York hospital for mental disorders. After the hospital released him in 1886, Welch offered him a research position while he recovered.

Welch's unswerving support helped Halsted start his career, but Halsted became shy and reticent even with his students, and in surgery he stressed a whole new method to control of bleeding, absolute cleanliness and careful reconstruction of tissue.

Halsted's knowledge of surgical anatomy and dissection, which he passed on to his students by operating before them on an old wood army hospital table left over from the Franco-Prussian War, was unparalleled, his technique precise. Today, many are familiar with the eponymous "Halsted radical," the initial life-saving surgical treatment for breast cancer, which he first described in 1891.

Halsted revolutionized surgery by insisting on skill and technique rather than brute strength. Using an experimental approach, he developed new operations for intestinal and stomach surgery, gallstone removal, hernia repair and disorders of the thyroid gland.

Thanks largely to Halsted, surgeons worldwide began wearing gloves during operations. One of his nurses, Caroline Hampton (whom he later married) complained that the mercuric chloride she was supposed to wash with gave her a rash. He asked the Goodyear Rubber Co. to try to make two pairs of thin rubber gloves to protect her hands. His surgical assistants were quick converts and began to wear them during operations, swearing that the gloves made them more dextrous. The idea that the gloves also might help in germ control actually didn't occur to any of them until years later.

Halsted had been at Hopkins seven years before he convinced the trustees that he had kicked his drug habit. They made him full professor of surgery in 1892. Until then, he had been given the title of “acting professor.” But about six months after Halsted was promoted, he confided in Osler that he was still taking morphine.

He remained addicted the rest of his life.

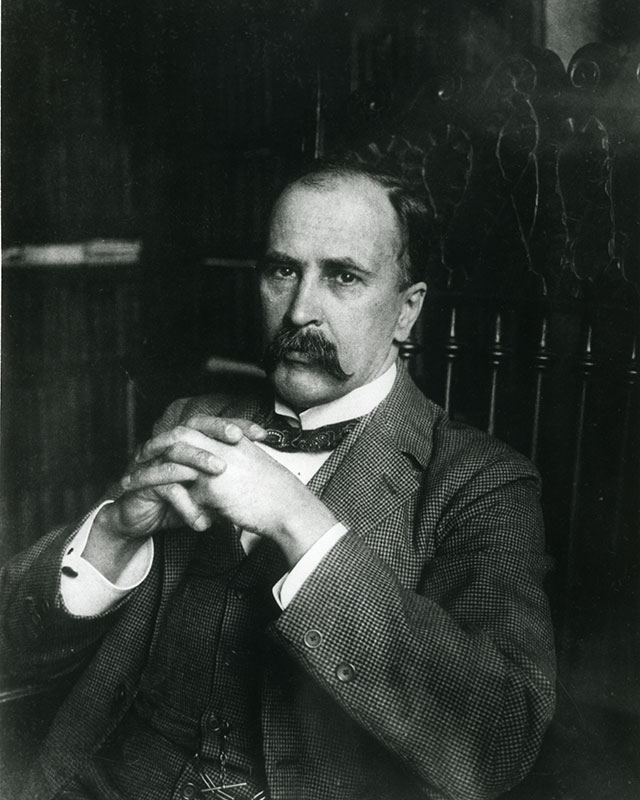

William Osler (1849 – 1919)

Osler arrived at Johns Hopkins in 1888 as physician-in-chief. A British Canadian, Osler was already considered America's premier doctor and was known as a superb clinical teacher.

Billings, the hospital's planner, generally is credited with having recruited Osler, but according to Simon Flexner, Welch's biographer, Osler was actually a second choice. When Welch pleaded Osler's case, Billings agreed with reluctance, believing Osler to be too interested in pathology, a field Welch had well covered.

Billings stopped off between trains in Philadelphia and went to Osler’s apartment to ask him to take charge of the medical department of the Johns Hopkins Hospital and Osler said yes without hesitation. This very short job interview changed the course of American medicine.

Osler was famous for using mnemonics to help his students remember what they needed to know. Four F's, for instance, lead to typhoid fever, he told them: fingers, food, flies and filth. His 1892 text, Principles and Practice of Medicine, became the landmark text of internal medicine and has been continually updated.

A short, wiry man with a handlebar mustache, Osler had an uncontrollable urge to pull practical jokes that constantly got him into trouble. Two years before he arrived at Hopkins, he had tricked a respected medical journal into printing an outlandish, bogus paper, and after that, the journal’s editor refused to publish Osler or take his work seriously.

Osler remains the Will Rogers of the medical world, and a column dedicated to his memory, “Osleriana,“ was launched in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1986. He was the first to say, “A physician who treats himself has a fool for a patient.”

Perhaps Osler's greatest contribution to medicine was the establishment of the medical residency program, now the norm in most training hospitals. Through this system, doctors in training make up much of a hospital's medical staff.

Osler also instituted another first by getting his medical students to the bedside early in their training; by their third year they were taking patient histories, performing physicals and doing lab tests instead of sitting in a lecture hall, taking notes. He once said he hoped his tombstone would say only, “He brought medical students into the wards for bedside teaching.”

He himself liked to say, “He who studies medicine without books sails an uncharted sea, but he who studies medicine without patients does not go to sea at all.”

Osler advocated good nursing, hygiene and prevention practices, and his medical stature helped him convince U.S. doctors to prescribe only drugs proven to be effective. He also fought against low-standard profit-making medical schools before he left for Oxford in 1905.

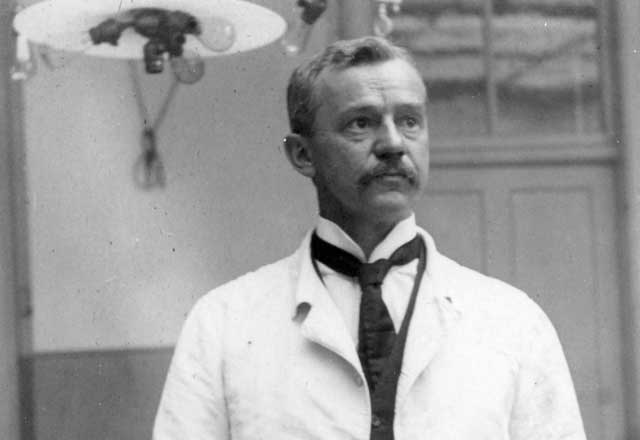

Howard Kelly (1858 – 1945)

Osler brought Kelly, a skillful gynecological surgeon, into the fold in 1889 from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School. Kelly was a fundamentalist Christian who read the Bible in the original Greek and Hebrew, and called a prayer meeting before every operation.

Kelly, only 31 when Hopkins hired him, gave his house staff, the gynecology residents, great responsibilities, much as Osler did. Kelly is credited with establishing gynecology as a true specialty; he concentrated mainly on new surgical approaches to women's diseases and to understanding underlying pathology.

He discovered several treatments and invented numerous medical devices, including a urinary cystoscope. When radium was discovered, Kelly was among the first to try it for cancer treatment (he is said to have gotten a sample straight from Marie Curie), and he founded the privately owned Kelly Clinic in Baltimore, once one of the country's leading centers for radiation therapy. He introduced the use of absorbable sutures to Hopkins, and was partly responsible for bringing the German artist Max Broedel, the father of medical illustration, to Baltimore. Broedel later headed the nation's first Department of Art as Applied to Medicine, at Johns Hopkins.

In addition to medicine and religion, Kelly had many interests. He and his wife had nine children. He collected exotic varieties of snakes, and was recognized as an expert among amateur herpetologists. Social reform attracted his attention as well. He fought against organized prostitution and worked diligently to help rehabilitate sex workers. He was an avid Bible quoter who frequently locked horns with the irreverent Baltimore columnist H.L. Mencken.

But, Mencken admitted (writing under a pseudonym), “Put a knife in [Kelly’s] hand, and he is at once master of the situation, and if surgery can help the patient, the patient will be helped.”