When Felicia Diggs-Hudson saw that one of her family members was battling depression, she searched for resources. A friend told her about the Congregational Depression Awareness Program (CDAP) at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, which disseminates via houses of worship valuable information about depression to people that it directly and indirectly impacts.

“I needed to find a way to be there for my family,” says Diggs-Hudson, an associate minister at the New Israelite Family Worship Center in Baltimore. “There are so many people that battle with depression and you would never expect it.”

Diggs-Hudson says she was taught to see depression as “a lack of faith,” but CDAP has changed that.

“If someone was battling mental illness, it was interpreted as God punishing you or as evil spirits overtaking you,” she says. “It was taught that you needed deliverance after true repentance. The truth of the matter is God placed people on Earth to study and become mental health professionals to help be a part of the healing process, just as if you were battling a physical illness. I’ve learned that the only way you can be healed is if you reveal. If you choose to remain silent, all you are going to do in your silence is continue to hurt and the illness will worsen.”

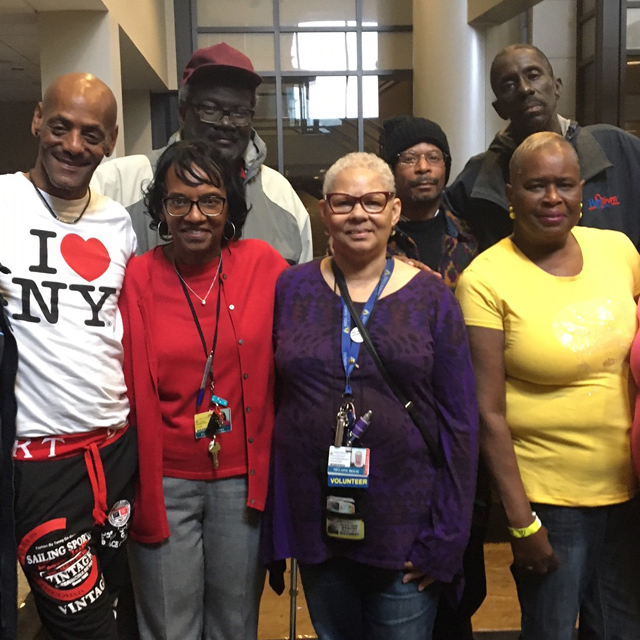

Nineteen church leaders representing 12 Baltimore congregations participated recently in a five-week, 10-hour training. The training includes an overview of the signs and symptoms of depression, options for medical and psychological treatment, personal stories, theological reflections, effective listening strategies and self-care tips. The program also includes local and national resources from the National Alliance on Mental Illness and the Pro Bono Counseling Project.

W. Daniel Hale, Ph.D., the founder and director of CDAP, started the program to reduce mental health stigma in faith communities and teach leaders how to help their congregations. Denis Antoine, M.D., CDAP co-director and an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, collaborated with Hale on developing the CDAP’s curriculum.

“Too often, people aren’t recognizing mental illness as a medical condition,” Hale says. “Many see it as some sort of moral or spiritual failure. If the religious leaders speak up, the congregation will follow.”

Hale and Antoine teach faith leaders that mental illness is a condition just like hypertension or diabetes, and Hale says “it can cripple your personal and professional life. It can be life limiting and even life threatening. Too many people don’t get the professional care they need.”

CDAP volunteers are taught how to recognize depression among congregants. They also learn how to get professional help for congregation members and how to give them hope.

“We talk about the various ways to access care and about what organizations are available to help support people,” Hale says. “We also talk about how to get care if insurance and finances are a problem.”

Kimberly Monson, CDAP’s coordinator, says the program works because faith organizations play large roles in Baltimore communities.

“People listen to and respect their faith leaders,” Monson says. “If the faith leader can help reduce the stigma and can talk about it openly within their congregation, that can help.”

After participating in the training program, Jerry Diggs, bishop at New Israelite Family Worship Center, says he noticed that there were several people with mental health issues in his ministry.

“I’ve learned that people have difficulty saying they have a mental illness because of trust factors,” he says. “I’m learning how to understand the illness and its limitations. We’re working to train our leaders so they can educate the members and bring mental health awareness to the ministry as a whole.”

The Rev. William Johnson Jr., Johns Hopkins Medicine’s community chaplain, is one of the program’s trainers. He facilitates active listening training and discusses religious connections.

“Mental health issues are serious in any community, but within the African American Christian community, they often go unaddressed,” Johnson says. “We’re teaching leaders how to recognize the issue and address that issue. It starts with listening. Listen twice as much as you’re speaking, and listen for feelings. Make sure the person feels they have been heard. Don’t try to fix it. Just listen.”

Johnson says it’s important that church leadership knows how to respond to whatever is brought to it.

“People are more likely to go to the pastor before they go to anyone else,” Johnson says. “They need to know it’s OK to advise someone to see a therapist or counselor.”

Pamula Yerby-Hammack, executive pastor at the City of Abraham Church and Ministries in Baltimore, is also a CDAP trainer. She shares her personal story of depression: In the fall of 2012, Yerby-Hammack had a sudden onset of depression and was admitted to the Sheppard Pratt adult day program for two weeks.

“The church always taught us that we could handle this by praying, fasting and scriptures,” she says. “I’m still a great proponent of prayer and scriptures, but I also know the condition I have needs medical intervention just as if someone had a heart issue.”

Yerby-Hammack says sharing her story is her “mission from God.”

“I knew it was a story that needed to be told,” she says. “It encourages other people to share their stories, and it helps people become more open. I tell people that it’s OK to get the help you need. Putting together the medical and spiritual has helped me to live a better life. I help people to see that mental illness is an illness that can happen to anyone.”

Yerby-Hammack says she’s glad to see church leaders participate in the training program because when pastors speak their congregations hang on to what they say.

“It’s a great way to get a good message out, where you’ve got an established audience,” she says. “Each congregation represents so many families. I hope they take the information back to their communities. It’s an each one reaches one kind of thing.”