No-Burp Syndrome: Bringing Back the Burp

Johns Hopkins laryngologist Lee Akst treats patients with retrograde cricopharyngeal dysfunction.

Otolaryngologist–head and neck surgeon Lee Akst

In late 2019, the calls started trickling in, and eventually they became a steady stream, says Johns Hopkins laryngologist Lee Akst. Although the details from each caller varied, the gist of their stories was the same: None of them could burp.

Many of the patients who found Akst were just learning about this condition medically referred to as retrograde cricopharyngeal dysfunction, or RCPD — and more casually called no-burp syndrome. People who were enduring the malady found a small but kindred community online on a prominent social media platform.

“The word got out that I treat no-burp syndrome,” Akst says, “and now I see at least three or four patients with it every month.”

In characterizing the experience of his patients, Akst explains that RCPD is more of a discomfort than a disability, but those with this condition can suffer significantly from its effects.

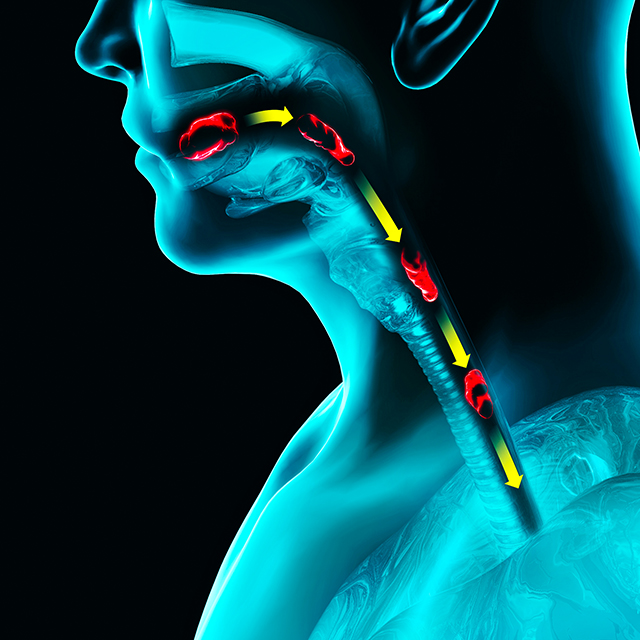

Patients with RCPD cannot orally expel gas, and this can cause them significant pain, Akst says. The audible gurgling from trapped gas can also lead to social anxiety. His patients have shared numerous anecdotes about having to leave events early because of their discomfort, or being embarrassed because other people could hear their digestive noises. With no other options, patients often administer their own self-treatment called “air vomiting,” in which they induce vomiting simply to expel excess air.

Initial attempts at diagnosis of patients may include esophagoscopy, videofluoroscopic swallow evaluation, and manometry. Results typically aren’t remarkable, Akst says, and some clinicians may tell them there’s nothing wrong. But those with RCPD don’t always need to suffer, he says.

As one of the relatively few otolaryngologist–head and neck surgeons treating the condition, he offers a therapy that can sometimes solve this problem permanently. When patients who suspect they have RCPD book an appointment with Akst, he listens to their medical history to confirm that their symptoms match the disorder’s profile. After making sure that they have no swallowing problems or reflux — both of which can worsen with RCPD treatment — they book an appointment for an outpatient procedure.

Akst prefers to perform the procedure in an operating room and to place patients under general anesthesia to ensure precise treatment. He injects the cricopharyngeal sphincter with botulinum toxin and dilates it with a balloon. These steps relax the sphincter, allowing gas from the esophagus to escape through the mouth as a burp.

For the first few weeks after treatment, Akst says, burping can be “exuberant,” with patients having little control over escaping gas. Passing food through the sphincter while swallowing might also feel slower, and patients might experience increased acid reflux. But over time, these side effects tend to decrease. Although the effects of the botulinum-toxin injection wear off after several months, about 90% of RCPD patients continue to burp normally, potentially because they have relearned how to control the cricopharyngeal sphincter, Akst explains.

After an initial follow-up at three weeks after their injection, most patients won’t need further follow-up. For those who don’t experience relief after a single injection, a second one is often curative, Akst says. He and his colleagues keep a prospective database to track outcomes after RCPD treatment to optimize dosing.

“Some of my happiest patients are those with RCPD, since this treatment can be lifechanging for them,” Akst says.

To refer a patient, call 443-997-6467.

For Clinicians Clinical Connection

Clinicians, discover the latest in research and clinical innovation from Johns Hopkins experts. Access educational videos, articles, CME courses and other resources from our world-renowned institution.

Related Reading

-

Research Advances in Head and Neck Surgery at Johns Hopkins

Physicians in the Johns Hopkins Division of Head and Neck Surgery are advancing clinical research in their field. The following are just a few developments taking place.

-

Johns Hopkins Swallowing Center Offers Patients Advanced Approaches

Whether using an infinity symbol-shaped balloon during dilation or employing the latest swallowing therapies, the team’s experts offer a vast range of options for patients with swallowing conditions.