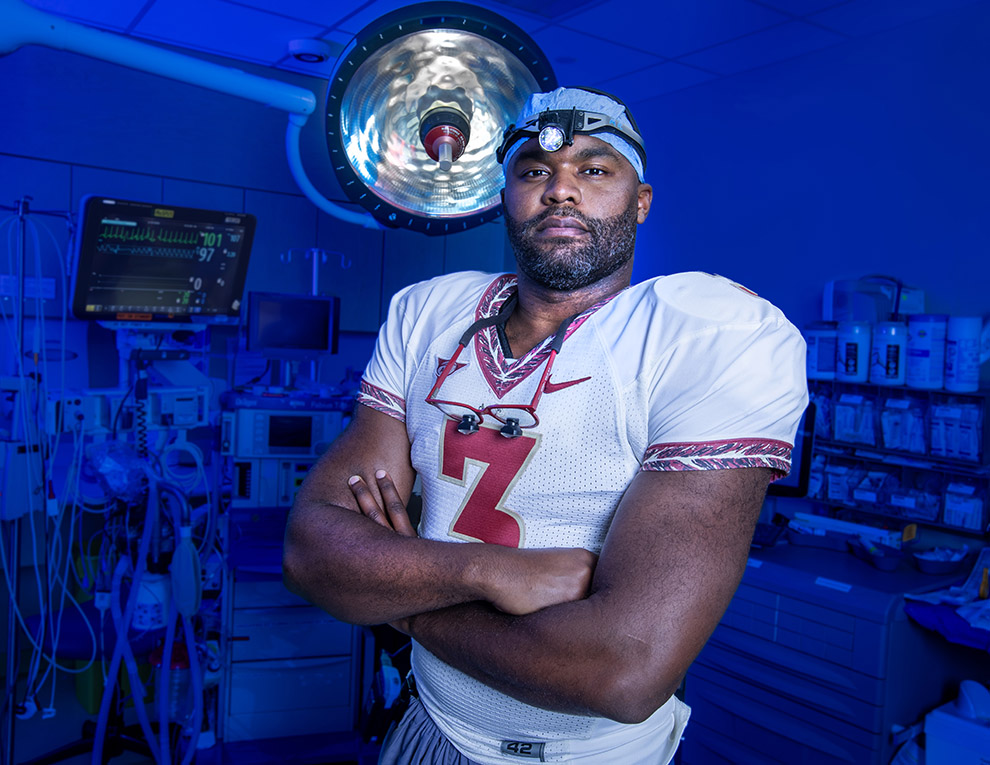

Myron Rolle’s Journey from Football to Brain Surgery

Myron Rolle, M.D., was 11 years old when one of his brothers gave him Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story.

Rolle devoured the autobiography recounting how Carson grew from a poor background into a world-renowned neurosurgeon. At 33, Carson became the youngest chief of pediatric neurosurgery in the United States at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center in Baltimore.

“Dr. Carson’s story stuck with me, because not only was he very intelligent, but he also was Christian, like I am,” says Rolle, now a pediatric neurosurgery fellow at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Florida. “He had parents who focused on education. His mother made him and his brother read all the time. She was not well educated herself, but was very committed to his intellectual development, just like my parents were. He also had a bit of a temper growing up. He got into some fights and got in trouble in school, and I saw so many parallels of his story. I was like, man, this guy sounds a lot like me.”

Rolle already had ambitious goals, but that’s when Carson joined football great Deion Sanders in inspiring this entry in Rolle’s notebook:

When you grow up:

- Play football in the NFL

- Become a neurosurgeon

Those goals fueled a life of high-profile attention, occasional anger and remarkable achievement.

High Achiever

Rolle was a star from his early days. An exceptional athlete with cousins who played in the NFL, he was driven by his family to be successful in academics as well.

Although he was born in Houston, Rolle spent some of his youth in the Bahamas, where his family was from and family and friendships were plentiful.

“The Bahamas is about 90% black, and you look to the left and to the right, you're related to somebody, or you went to church with somebody, or you get your hair cut by that person,” Rolle says.

In coming to America, Rolle’s father, Whitney, set an expectation for achievement for his five sons: “Be so good they can’t deny you.”

“That meant to be great in the classroom, be great on the football field, be great as a leader, as a thinker, as a friend, as a motivator, really, there was no part of my formative years where I could be anything less than the best,” Rolle says. “I think that mindset helped me normalize what perfection or greatness looked like, and it became habitual to strive for that.”

Although there were missteps and bouts of isolation to avoid impediments to his goals, Rolle took those lessons to heart.

In high school, he became a recruiting sensation, sorting through 83 football scholarship offers to choose Florida State.

The 2% Way

Florida State offered full support for Rolle’s goals toward a career in both football and medicine, and pursuit of a Rhodes Scholarship. It also provided the philosophy that has guided his life ever sense.

As Rolle became a star defensive back for the Seminoles, he learned a philosophy from defensive coordinator Mickey Andrews: Strive to get 2% better at something each day.

“That 2% way, that’s the ethos that I live life by, taking small steps every day toward getting better and being a better version of yourself,” says Rolle, whose autobiography, The 2% Way, was published in 2022. “Small, incremental gains — once you add them all up — you realize how much progress you’ve made. It also feels like you won the day, if you’re just able to get a little bit better.”

Rolle’s book recounts how he applied the philosophy to everything from pass-defense technique as a football player to mastering shunt incisions as a surgeon to becoming a better father to his two sets of twins.

“Football has not only taught me to frame life that way, but it also taught me some of the fundamental pillars of being successful as a physician, as a father, as a husband, as a community leader,” Rolle says. “Those are discipline, focus, hard work, communication, overcoming adversity, mitigating pressure, being adaptable and adjustable.”

Conflicting Goals

As Rolle excelled in both football and academics at Florida State, his goals began to collide.

The Rhodes Scholarship is a prestigious, postgraduate program established in 1902 where students from around the world are chosen to study for a year at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. Among the famous recipients are President Bill Clinton, former NBA star and U.S. Senator Bill Bradley and singer-songwriter-actor Kris Kristofferson. Fewer than 2% of applicants are chosen. Rolle was one of them.

But accepting the scholarship and a year in England meant taking a year off from football and postponing entry into the NFL Draft where he was projected as a first-round pick. Rolle wrestled with the choice before accepting the scholarship and spending a year at Oxford.

“The decision ultimately came down to thinking about my future and also thinking about young people who look at my story and find inspiration in it the same way I found inspiration in Bill Bradley, the same way I found inspiration in Ben Carson.”

Rolle remained dedicated to football, working out in early morning hours to maintain his strength and skills. He expected to pick up his football career where he left off when he returned.

But it didn’t work out that way.

Rolle was frustrated by suggestions that he wasn’t dedicated enough to football, that he had quit on his team. He wasn’t drafted until the sixth round by the Tennessee Titans.

“It was definitely a blow to my athletic career by spending that time in Oxford,” Rolle says.

Fighting for a Spot

Rolle dedicated himself to winning an NFL roster spot, but despite winning praise from coaches and fellow players for his performance in practices and preseason games, he was assigned to the practice squad where he spent three seasons with the Titans and Steelers.

Rolle firmly believes NFL teams treated and evaluated him differently because of his stature and experiences. He recounts how as players were stretching, coaches would ask his teammates about defensive schemes or recovering from an injury. When they got to Rolle, they’d ask him about meeting Clinton or traveling with celebrities on a humanitarian trip to Africa.

As Rolle was trying to make the NFL, the dangers of concussions were becoming a more prominent issue in the sport. Several former players who died were found to have a condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurodegenerative disease believed to be caused by repeated trauma to the head.

Rolle believes the image-conscious NFL didn’t want to risk the Rhodes Scholar’s dream of becoming a surgeon being dashed by a head injury in the league.

“If something had happened to me where I was no longer able to fulfill that dream, then it would be a terrible media hit for the NFL,” Rolle says. “It’s a league that wants to protect its image at all costs.”

Rolle was released by the Steelers in 2012 and gave up on his pursuit of the NFL.

“They had this mindset that we’re helping Myron,” Rolle says. “You don’t need this sport. You’re going to be fine. One day, you’re going to be a brain surgeon. I couldn’t believe the sport I loved for so long was being taken away from me because I had other options once I was done playing.”

Strong Women

In his book, Rolle writes that it was his mother, Beverly, who gave him the needed nudge to move on from the NFL to medicine. She showed him that old notebook where he had written his goals, telling him it was time to cross off the first one and move on to becoming a neurosurgeon.

Rolle felt a weight lift from him and the promise of the next challenge fill him.

Beverly was one of many strong women who have sustained Rolle throughout his life.

“Women, especially women of color, have been my greatest champions my entire life,” Rolle says, citing friends from high school, college, Oxford and medical training. “These women have protected me. They have shielded me. They have seen my blind spots and have looked out for me.”

Rolle’s wife, Latoya — a dentist whom he met through a Black medical professional networking site — persuaded him to push through his doubts and write his autobiography.

“Just like you looked at Ben Carson’s story and saw a winner, you can be that for somebody else,” he remembers her telling him.

No Regrets but More Goals

After medical school at Florida State, Rolle completed a neurosurgery residency program at Harvard before joining Johns Hopkins All Children’s.

When his draft stock dropped upon his return from Oxford, Rolle had doubts about whether he had made the right choice.

“Now, looking at how my life has transpired and how people come up to me and say, we write biographies on you and I teach my son or daughter about you and that makes all the difference. It makes me believe that I made the right choice.”

Rolle has achieved elite football success, won the Rhodes Scholarship, formed a growing family and become a brain surgeon.

But he still has goals, even if they are not in his childhood notebook. He ends his book writing about changing the world.

“Global neurosurgery is a tough course to sled, because when people think about global health, it's often directed toward infectious disease, AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, things of that nature, and less about a subspecialty like neurosurgery,” Rolle says of this ambition. “But coming from the Bahamas, I understand when people have a brain injury — stroke, trauma, hydrocephalus, any sort of brain central nervous system disease — it's often seen as a death sentence.”

Rolle works with international organizations to seek more training, resources and support for brain health around the world, particularly the Caribbean.

For Rolle, everything traces back to those lessons his family instilled so long ago, the lessons he now imparts to his own children.

“Keep pushing the Rolle name forward,” he says. “Our last name came from a slave owner in Exuma, Bahamas, a white man from Great Britain. All these slaves took the name Rolle, and now we've taken this last name Rolle to a place of respect, honor, integrity and success. We want you to keep that going.”