Kimmel in the Community

THE CANCER CENTER'S OUTREACH TO THE COMMUNITY HAS ALWAYS EXISTED, BUT IT HAS CHANGED AND EXPANDED OVER ITS 50-YEAR HISTORY.

COMMUNITY OUTREACH was initiated in 1978 to make sure advances against cancer made at Johns Hopkins were available to patients throughout Maryland, across the U.S. and around the world.

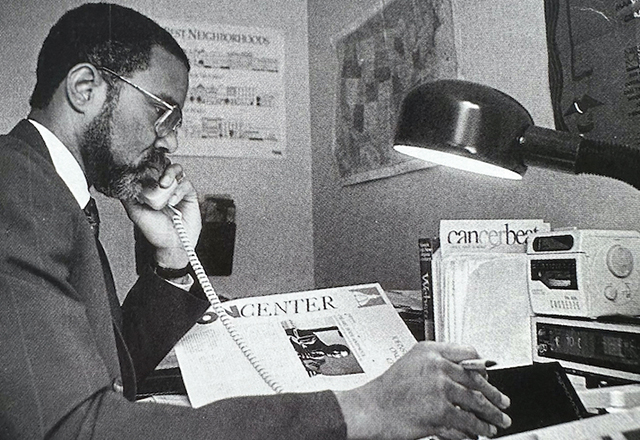

ETTINGER

ETTINGERDavid Ettinger, M.D., one of the Cancer Center’s first fellows and faculty members, spearheaded the initial efforts to engage cancer experts in the community. It began informally.

It was not unusual for Ettinger to field multiple calls in a day to help physicians in Maryland and other states who were treating patients with cancer. There was a constant barrage of faxes and phone calls, such as a physician in New Jersey treating a patient with lung cancer calling to discuss the latest treatment options. Another from Western Maryland wanting to know the best possible use of a cancer-fighting drug; someone else with a question concerning the current guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network for small cell lung cancer. Ettinger made time for all of them.

Telephone and face-to-face communication were the only tools for outreach.

“When I joined the oncology team in 1975, there were no fax machines and no computers,” says Ettinger.

He began hosting monthly meetings open to all cancer specialists in the community to come to Johns Hopkins and hear about research advances and to discuss challenging cases.

Today, in the era of computers and smartphones, most are familiar with the term virtual medicine, but decades before these technologies were available, Ettinger and others had already begun to envision them.

In 1989, collaborative radiation oncology services were established among the Cancer Center and St. Agnes Hospital in Baltimore and Chambersburg Hospital in Pennsylvania. In the late 1990s, with the advent of computers, Ettinger and other experts began to use sophisticated computer connections to review patient X-rays and CAT scans from as far away as Singapore. Ettinger called it telemedicine.

At the same time, we began to see that working with community physicians was not enough. There were many people, particularly those who did not have health insurance, those living in poverty and racial minorities, who were suffering in silence. They were not seeking help for health issues.

WILSON

WILSONWe began in our own neighborhood. Reverend Doug Wilson, director of community outreach, worked with local clergy to bring cancer screening and detection programs to the communities of East Baltimore.

In 1999, Cancer Center social worker James Zabora took over as director of community outreach.

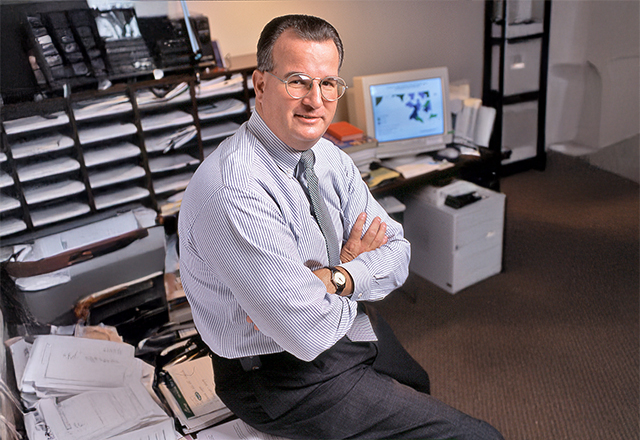

ZABORA

ZABORA“I looked out of my office window directly into the neighborhoods with possibly the highest cancer rates in the nation. I realized, as a comprehensive cancer center, we had an obligation to apply our knowledge to help these communities,” said Zabora.

In the late 1980s, an analysis of health disparities based on ZIP codes confirmed what Zabora already suspected. The life expectancy for a resident of low-income neighborhoods along Madison/East End was 64, compared with 84 for residents of the higher-income neighborhood of Roland Park, even though the communities were only 5 miles apart.

He began working with churches, community centers and local organizations to provide education about cancer screening.

In 2002, with the establishment of the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund (CRF, see Maryland Confronts Cancer), Zabora’s efforts were aided by a $1.5 million public health grant to expand outreach, with a particular focus on Maryland’s most common cancers.

Zabora and team took on Baltimore City’s prostate cancer death rates — the highest in the nation — providing physical exams and PSA (prostate specific antigen) tests to 2,500 African American men. The grant meant that, if a cancer was detected, treatment at the Kimmel Cancer Center could be provided at no cost.

Building upon Reverend Wilson’s earlier outreach, Zabora continued partnering with ministers and community activists. Cancer screening sites opened at the Bea Gaddy Center, Garden of Prayer Baptist Church, Morgan State University and the Korean Resource Center, and thousands were being reached.

FORD

FORDJean Ford, M.D., joined the Kimmel Cancer Center in 2006 as director of community programs and cancer health disparities research. He was focused on understanding the barriers to care and increasing participation in cancer prevention and treatment trials.

Under his leadership, the East Baltimore Medical Center was set up as the headquarters for the program.

“We wanted our staff to be located right in the community,” said Ford.

Connie Ziegfeld, former assistant director of nursing for the Kimmel Cancer Center, worked with Ford as a clinical nurse specialist and case manager for the CRF-supported prostate cancer screening program.

Ziegfeld quipped that she didn’t know whether to say she was a public health nurse, patient advocate, travel agent, counselor or health educator. Community members said she was all that and more.

Years of working as an oncology and ambulatory care nurse allowed her to efficiently navigate the potentially restrictive factors that can block patients’ participation in their own health care.

“I’m doing something for a population that is frequently overlooked in our society,” she said. “It touches me positively every day.”

In 2010, the Kimmel Cancer Center established the Johns Hopkins Center to Reduce Cancer Disparities with the goal of providing all Maryland communities equal access to cancer prevention and treatment services.

SCOTT

SCOTTOne project, led by Theron Scott, assistant director of community education, focused on smoking cessation. Scott, an African American and former two-pack-a-day smoker, took a smoking cessation program to Latrobe Homes, an East Baltimore public housing development near Johns Hopkins. The program was so successful, it quickly expanded to other low-income neighborhoods

There was success. All of the efforts were making an impact. Overall, cancer death rates declined in our state, and the gap in cancer death disparities between African American and white Marylanders narrowed by more than 60% since 2001, far exceeding national progress. Like Albert Owens and Martin Abeloff before him, Kimmel Cancer Center Director William Nelson was committed to eliminating the gap.

LANSEY

LANSEYEnter Dina Lansey, M.S.N., R.N., Nelson’s choice to direct efforts to increase minority participation in clinical trials. Lansey, a seasoned expert in addressing racial disparities in cancer, developed ways to better measure and understand why many African Americans, women, elderly people with low income, and Baltimore City residents often chose not to participate in clinical trials.

Lansey began gathering data and identified cost and convenience of transportation as one barrier, launching a pilot project to provide free parking or taxi transportation to Baltimore City residents.

She also launched a clinical trials awareness campaign, including in-depth videos that explained clinical trials and offered patient testimonials, to help patients and families better understand the purpose of clinical trials and the value of considering them when making treatment decisions. She also instituted mandatory training for all clinical faculty and staff.

Under her leadership, Johns Hopkins became the first institution to use its electronic medical records to support conversations about clinical trials. Lansey matched minority and low-income patients to available clinical trials, and used a database to track reasons patients declined to participate. She used the information to help guide the development of ways to remove fixable barriers that kept patients from treatments that could help them. The system also documented that clinical trials were discussed with patients, and communicated names of interested patients to study teams.

Her action plan included collaborating with investigators as studies were designed to identify barriers to participation from the onset and develop targeted interventions aimed at those most in need.

Lansey’s efforts had promising results. The number of patients from Maryland treated at the Kimmel Cancer Center increased from 985 in 2010 to 1,231 in 2015, and the disparities gap continued to narrow. In 2015, 22% of Kimmel Cancer Center patients were African American, and just over 20% participated in clinical trials.

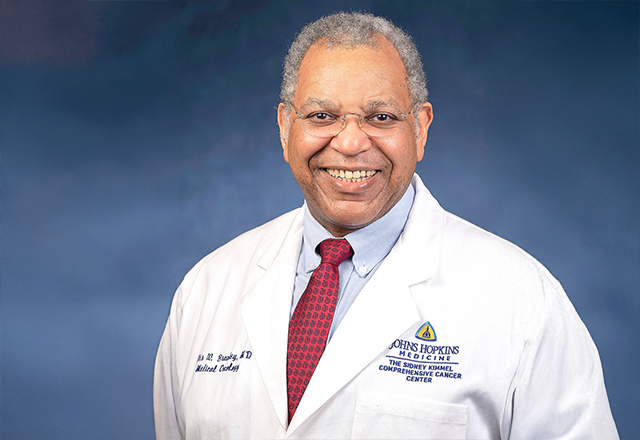

BRAWLEY

BRAWLEYIn 2019, the program again expanded with the recruitment of Otis Brawley, M.D., a nationally renowned authority on cancer screening and prevention, as director of community outreach and engagement. Brawley, a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor, had been chief medical and scientific officer for the American Cancer Society and director of the Georgia Cancer Center at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta.

Together, Lansey and Brawley have taken the program to a new level, establishing a Community Advisory Board and recruiting clinical health educators.

In 2022, they launched a community health education program, with the clinical health educators providing live webinars and in-person sessions to educate communities about healthy living, ways to reduce cancer risk and cancer screenings. The program was launched with a series of sessions offered to the more than 900,000 Johns Hopkins Community Physicians patients through its network of community practices throughout Maryland and Washington, D.C.

Between March 2022 and January 2023, they hosted 10 events and reached more than 1,600 citizens with presentations on colorectal and breast cancer awareness, cancer risk reduction, HPV awareness, cancer and nutrition, and the dangers of vaping. Upcoming sessions on nutrition and exercise are planned.

They seek answers to some very important questions: How do race, income and ZIP code influence life and death? Brawley notes that ZIP code may be more important than genetic code in predicting health outcomes.

Our experts continue to identify pockets of cancer health disparities and work to develop effective interventions. In addition to Baltimore City, some of Maryland’s rural areas are highest in cancer deaths and new cases, which we are addressing. With the Kimmel Cancer Center’s expansion to the National Capital Region at Johns Hopkins’ Sibley Memorial Hospital, additional outreach to Wards 5, 7 and 8 in Washington, D.C., which has some of the highest cancer rates in the country, has started.

Building upon efforts that began in 2003 to establish a collaboration between the Kimmel Cancer Center and Howard University Cancer Center in Washington, D.C., to address cancer burden in minority populations, new efforts have begun to ensure that the diversity of care providers reflects the diversity of people with cancer.

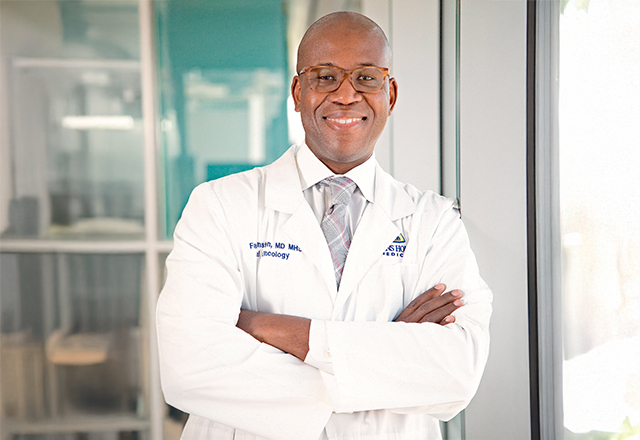

JOHNSTON

JOHNSTONFabian Johnston, M.D., M.H.S., and Mary Armanios, M.D., co-directors of the Center’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in Education and Training, organized efforts, including social justice dialogue, programs and outreach to historically Black colleges and universities in Maryland, to enhance recruitment, mentorship and retention of underrepresented trainees and faculty members at Johns Hopkins.

ARMANIOS

ARMANIOSToday, Community Outreach and Engagement has grown to embrace a full scope of outreach, from our community and patients to future scientists and clinicians, and it has become interconnected with every research program and clinical activity at the Kimmel Cancer Center.