Beating Pancreatic Cancer

KATHLEEN

In 1997, dark urine and annoying itching all over her body drove Kathleen, then 50, to see her doctor.

Her doctor suspected a gallstone. However, when routine surgery at a community hospital near her home to remove the gallbladder resulted in complications with her small intestine, pancreatic cancer was detected.

JAFFEE

JAFFEEThe surgeon broke the devastating news to Kathleen’s husband and 25- and 21-year-old daughters. He recommended Kathleen go to Johns Hopkins for surgery. The surgeon told the family that “Hopkins surgeons have the most expertise in doing this surgery,” recalls Kathleen.

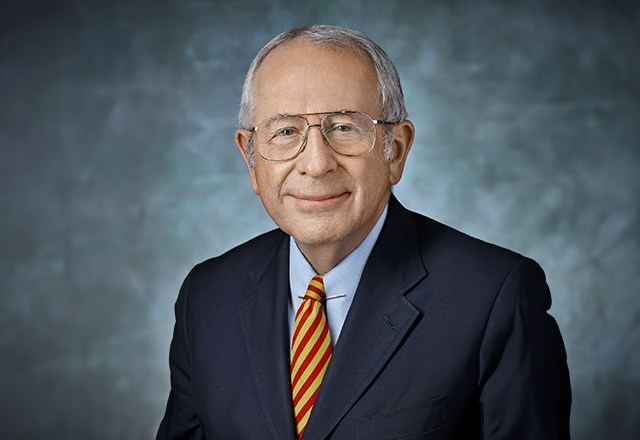

The next day, she was transferred by ambulance to Johns Hopkins, and met with world-famous surgeon John Cameron. In a surgical procedure known as the Whipple, he removed Kathleen’s pancreas, part of her stomach and several lymph nodes.

DONEHOWER

DONEHOWERThe Whipple is the primary surgical treatment for pancreatic cancer, and Cameron pioneered significant improvements to the surgery. Under his direction, Johns Hopkins earned the reputation as the best in the world for pancreatic cancer surgery and for training the next generation of surgeons. These improvements made the complex surgery safe, and dramatically reduced complications.

The lymph nodes are small glands that are part of the immune system and carry cells and fluid to other parts of the body. They provide a means for cancer cells to spread from the original tumor to other organs. Examination of the lymph nodes removed during Kathleen’s surgery revealed that they contained cancer cells, meaning the cancer had begun to spread and would not be cured by surgery alone.

“I wasn’t familiar with pancreatic cancer. I didn’t know anyone who had it, so I really didn’t understand how bad it was,” says Kathleen. “I was shocked when I learned the statistics.”

ZHENG

ZHENGShe still recalls the day she asked Cameron if the dismal pancreatic cancer survival rates she read about were true. He told her they were, but he also told her she could be the one to beat the odds.

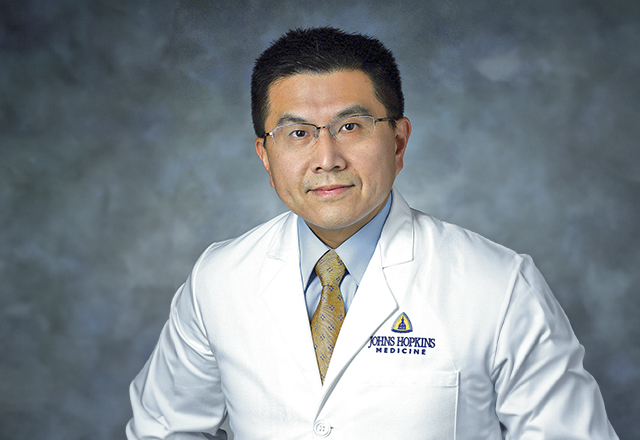

She received chemotherapy to help mop up any remaining cancer cells. Gastrointestinal cancer expert Ross Donehower, M.D., told Kathleen about a clinical trial of a new cancer vaccine developed at the Kimmel Cancer Center by leading pancreatic cancer researcher Elizabeth Jaffee, M.D., co-director of the Skip Viragh Center for Pancreas Cancer Clinical Research and Patient Care.

“He said it might keep my cancer from coming back,” says Kathleen. Given the statistics she read, she wanted to give it a try. She was the eighth patient to receive the vaccine.

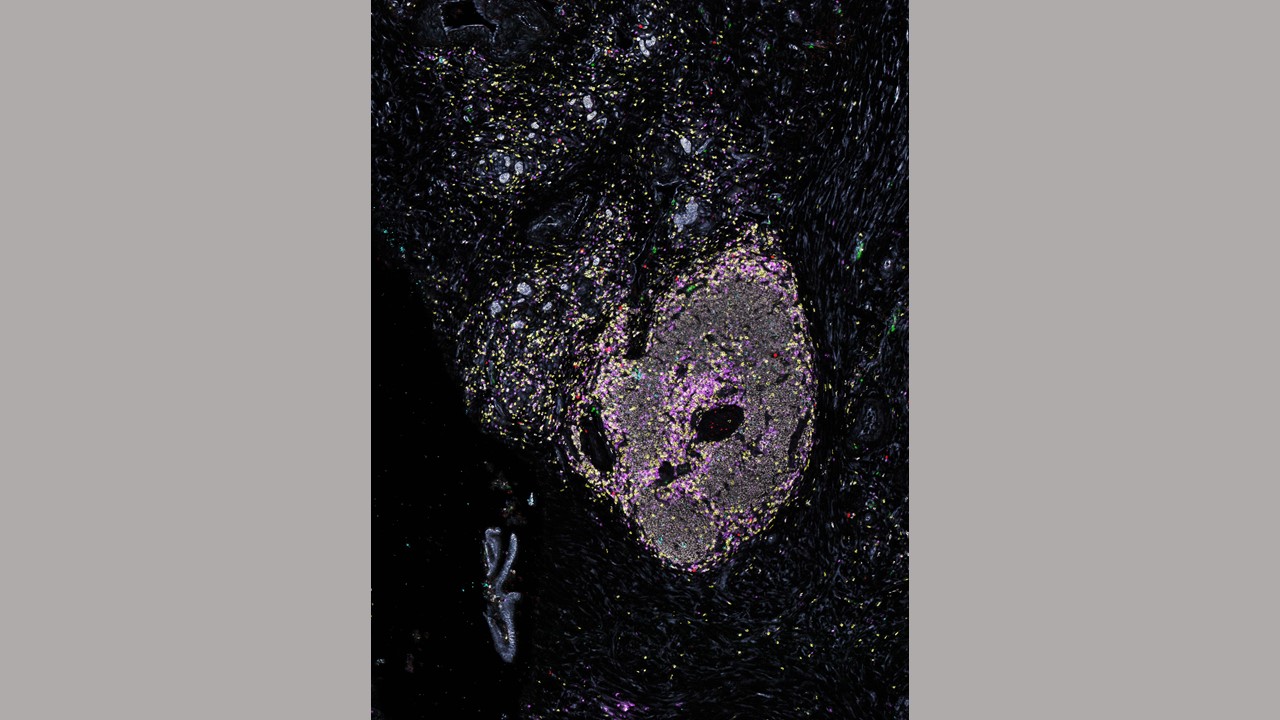

The pancreatic cancer vaccine works by supercharging the immune system, causing immune cells to seek out and kill cancer cells, including hunting down and cleaning up surviving cancer cells or newly appearing cells anywhere in the body. With few treatments for advanced pancreatic cancer, the vaccine attracted worldwide attention when it was developed in the early 2000s. The clinic received more than 60 inquiries each month from patients hoping to receive the vaccine. After Jaffee appeared on TheDr. OzShow in 2011, the clinic was flooded with more than 1,000 inquiries.

“We were the only cancer center at the time doing this kind of work,” says Lei Zheng, M.D., who works with Jaffee on pancreatic cancer vaccines and other treatments for the cancer. He is also co-director of the Pancreatic Cancer Precision Medicine Center of Excellence, aimed at the quick translation of the latest research on vaccines and immunotherapy, molecularly targeted therapy, chemotherapy, radiation and surgical techniques to patients.

After receiving two doses of the vaccine, Kathleen developed a condition called TTP, which causes blood clots to form throughout the body. It was not caused by the vaccine, but it meant she would not be able to receive additional doses of the vaccine.

Remarkably, the two doses Kathleen received were enough, and 26 years later, she remains cancer-free.

“I remember the doctors telling me I had the strongest immune response of anyone in the clinical trial,” says Kathleen.

CAMERON

CAMERONIt is a complex process to activate the immune system to recognize pancreas cancer cells and simultaneously suppress mechanisms Kimmel Cancer Center researchers have revealed are co-opted by tumor cells to shut down the immune response. Jaffe, Zheng and the Skip Viragh Center team continue to study new approaches, including combining the vaccine with drug therapy or radiation therapy, and creating vaccines individualized to the unique molecular characteristics of a patient’s cancer.

Today, at 75, Kathleen is retired and enjoying her four grandchildren. She had one grandchild when she was diagnosed.

“I didn’t think I’d live to see her grow up,” says Kathleen.

She started making bunnies, cladding them in fancy dresses. She thought it would be a way for her granddaughter to remember her. Now, they are a lasting testament to her survival. Kathleen has made one for each of her grandchildren.

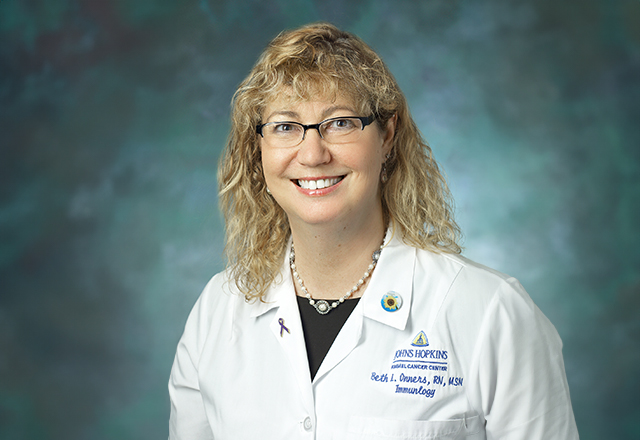

ONNERS

ONNERSIt wasn’t an easy journey, and there have been a few scares along the way, such as a spot that showed up on a CT scan.

“They never amounted to anything,” she says.

She is grateful to her doctor, Dan Laheru, M.D., co-director of the Skip Viragh Center, for being so thorough. After all these years, Kathleen still gets emotional when she thinks about her cancer battle. She has great respect for her doctors and nurses.

“Dr. Jaffee, Dr. Laheru, my nurse Beth Onners, I can’t say enough about them,” says Kathleen. “They are wonderful, top notch.”