A Game-Changer for Ovarian Cancer

Illustration by Francesco Ciccolella

Ovarian cancer is a notoriously difficult group of diseases to diagnose and treat. There is no effective screening method — most people have widely metastatic cancer when they start showing symptoms, and most patients die within five years. Additionally, the most lethal type — high-grade serous carcinoma — is the most common, and is the fifth most common cause of cancer-related death for women in the U.S.

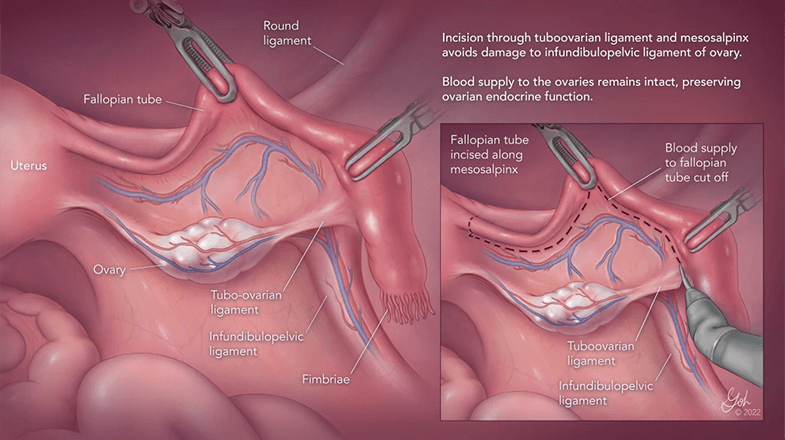

A new approach offers some hope in preventing this disease, which will affect 1 in 78, or 1%–2%, of women in their lifetimes. Salpingectomy (fallopian tube removal) is a low-risk surgery that can reduce the risk of ovarian cancer by as much as half. While the approach has not yet been widely adopted, the Johns Hopkins Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics is leading the way in its own clinics, and faculty members are working on national and international educational and advocacy efforts.

Although it was long believed in medicine that ovarian cancer originates in the ovaries, research from the past 20 years shows that most cases arise from precancerous cells in the ends of fallopian tubes.

“That finding is such a game-changer because it explains why we have been unsuccessful at detecting it and developing screening tests,” says Rebecca Stone, a gynecologic oncologist with expertise in ovarian cancer and director of the Kelly Gynecologic Oncology Service. “We’ve never really had the promise of prevention like this in medical history — that one could choose to remove an anatomic structure that has no known function after child-bearing to prevent a lethal cancer later in life.”

The fallopian tubes don’t serve any known purpose beyond a patient’s reproductive years, as opposed to ovaries, which still produce important hormones likely well beyond menopause.

The surgery, which takes minutes, can be electively performed at the same time as another planned intra-abdominal surgery, such as a hysterectomy or other post-reproductive gynecologic surgery. Patients interested in permanent contraception through surgical sterilization should be counseled about the option of salpingectomy in lieu of tubal ligation to reduce their lifetime risk of ovarian cancer, Stone says, as tubal ligation does not cut the risk nearly as much. She sees a lot of opportunity here, as 700,000 women a year elect to get tubal ligation surgery in the U.S. alone.

In 2015, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology released guidance recommending that patients undergoing certain surgeries be counseled about the option of concurrent salpingectomy for ovarian cancer prevention. Johns Hopkins has since adopted the procedure as best practice, providing salpingectomy to nearly 100% of patients undergoing hysterectomy and approximately 85% of patients opting for surgical sterilizations in the past year. This is substantially better than the national rates of 60% and 20% for hysterectomy and surgical sterilization, respectively.

Stone is now part of Break Through Cancer, which has a project that aims to expand awareness of and access to salpingectomy for ovarian cancer prevention as a means to decrease its death toll. The initiative includes specialists from Johns Hopkins, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research. In concert with this effort, Stone is also among the specialists working with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to write medical coding for prophylactic salpingectomy. At present, salpingectomy is not universally covered by all insurances, and fixing medical coding is the first necessary step toward removing that barrier.

An article published in JAMA in June by Stone and her main collaborators — Memorial Sloan Kettering gynecologic oncologist Kara Long Roche (a former Johns Hopkins faculty member) and Johns Hopkins general and critical care surgeon Joseph Sakran — made the case for salpingectomy and brought attention to the issues Break Through Cancer is tackling. The article is in the top 5% of all research outputs scored by Altmetric, an entity that measures online engagement with scientific articles.

Stone also organized an international task force of obstetric and gynecologic surgeons, gynecologic oncologists, pathologists and epidemiologists to similarly spread awareness and tackle barriers to care that exist on an international scale.

“We’re not talking about just changing practice for Johns Hopkins, we’re talking about changing practice for the U.S. and for the world,” Stone says.

For more information on salpingectomy, click here.

“We’ve never really had the promise of prevention like this in medical history — that one could choose to remove an anatomic structure that has no known function after child-bearing to prevent a lethal cancer later in life.”

Rebecca Stone