Major Renovation Upholds Johns Hopkins’ Status as Leader in Otolaryngology Surgical Training

For nearly a century, the Johns Hopkins Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery has maintained a temporal bone laboratory where residents, fellows and faculty can practice ear and skull base surgeries. During that time, the space has helped to uphold Johns Hopkins as a leader in surgical innovation and in head and neck surgery training. To ensure the department stays at the forefront of surgical training and research and adapts to changing needs of the specialty, the space has recently undergone major renovations and a name change.

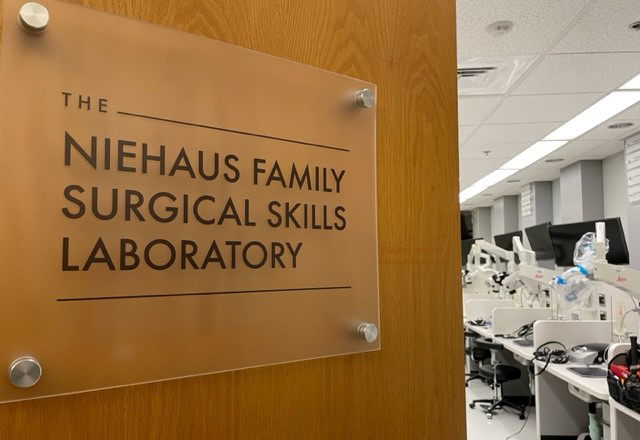

“As our specialty has broadened over the last 50 years, there has been a need for all otolaryngology subspecialities to have a place to do cadaveric and other simulated surgeries,” says neurotologist and lateral skull base surgeon Francis “Pete” Creighton, who helped oversee the redesign of what is now known as the Niehaus Family Surgical Skills Laboratory. “That led to the need to revamp the space and rethink its design to make it more applicable for our entire field and the future needs of surgical training.”

Residents are required to master many more procedures now than 20–30 years ago, yet they have increasingly limited time to train — and less autonomy, Creighton adds. “We hope this lab will ensure our trainees are getting the opportunity to hone their skills in a safe, easily accessible environment, so they can make the most out of every moment they have in the operating room while at Hopkins.”

With funds from the university, alumni and donors, the laboratory space on the eighth floor of the Ross Building was gutted down to the studs and rebuilt into what is now “a world-class surgical facility,” according to Creighton. The area has 18 flexible workstations (including an instructor station with video that can be projected for teaching), each with state-of-the-art surgical microscopes and 4K high-definition video display, as well as instruments and equipment to perform open and endoscopic surgical procedures. Learning stations are equipped with otologic drills and feature custom-built worktables with shelves, irrigation, suction and surgical grade overhead lights, all in an effort to allow for practice and training in all types of otolaryngology surgeries including sinus, voice, head and neck cancers, and microvascular reconstruction.

The lab held its inaugural temporal bone course in January, during which residents from Johns Hopkins and the University of Maryland were able to receive hands-on training in a range of otologic surgeries. Courses in laryngology and sleep surgery have recently been completed, with multiple courses in other subspecialities scheduled for later this year. The lab has hosted industry demonstrations of new surgical technology for a national audience, and already has been used for multiple avenues of research.

The space will enhance research capabilities for residents in ways beyond typical cadaveric dissections. For example, the lab also houses a virtual reality surgical simulator developed by Creighton and collaborators at Johns Hopkins’ Whiting School of Engineering, which residents can use at any time to practice their surgical skills. This work is funded by a Johns Hopkins Discovery Award focused on developing artificial intelligence-based coaching for residents and more objective assessments of residents’ skills.

“The ultimate goal is if a resident knows what cases they are going to be in on a Tuesday, they can go in the lab on a Monday, pull CT scans from those patients and practice virtual surgical simulations,” Creighton says. “Furthermore, we are working to develop methods to give them automated feedback on how they did compared to how an attending surgeon would have performed the procedure, and where they need to improve. We’re not entirely there yet, but we are getting closer, and this lab is a big step forward.”

The lab also will house a 3D printer, to allow production of low-cost anatomical models for training and practice, and a 3D navigation system to give lifelike training opportunities for sinus and skull base surgery, as well as allow the space to be used for robotics and computer vision research collaborations. “All of these things will position Johns Hopkins to continue to lead the way in surgical training, surgical innovation and surgical research,” says Creighton.

History of Johns Hopkins’ Temporal Bone Lab

Before it was called the Niehaus Family Surgical Skills Laboratory, Johns Hopkins’ temporal bone surgical training site was known as the Otologic Research Laboratory. Established in 1924, it was the United States’ first human temporal bone laboratory. By 1938, anatomist Samuel Crowe, Johns Hopkins’ first chair of otolaryngology, had amassed the world’s largest collection of temporal bones — 1,800 to be exact. The department has added to the collection over the decades, and the study of them has led to key discoveries, including early insights into the cochlear pathologies of age-related hearing loss correlating audiometric measurements with patterns of cellular degeneration and changes in bone tissue that lead to otosclerosis.

The lab was first located in a (since torn down) pathology facility and then in the Hunterian Building, says otolaryngology and neuroscience associate professor Amanda Lauer. Then, former Johns Hopkins otolaryngologist Howard Francis, who was working to catalog the temporal bone collection and restart human temporal bone research, and others had lab space adjacent to a dissection skills lab in the Ross Building. The Francis lab space was later demolished and incorporated into the new dissection skills lab expansion.