Long Haulers

Infants born with congenital heart defects, like Tyler and Jeremy Harshman, often require lifelong follow-up as they grow. Through relationships they’ve built over the years with their care team at Johns Hopkins, the brothers have found ‘a second home.’

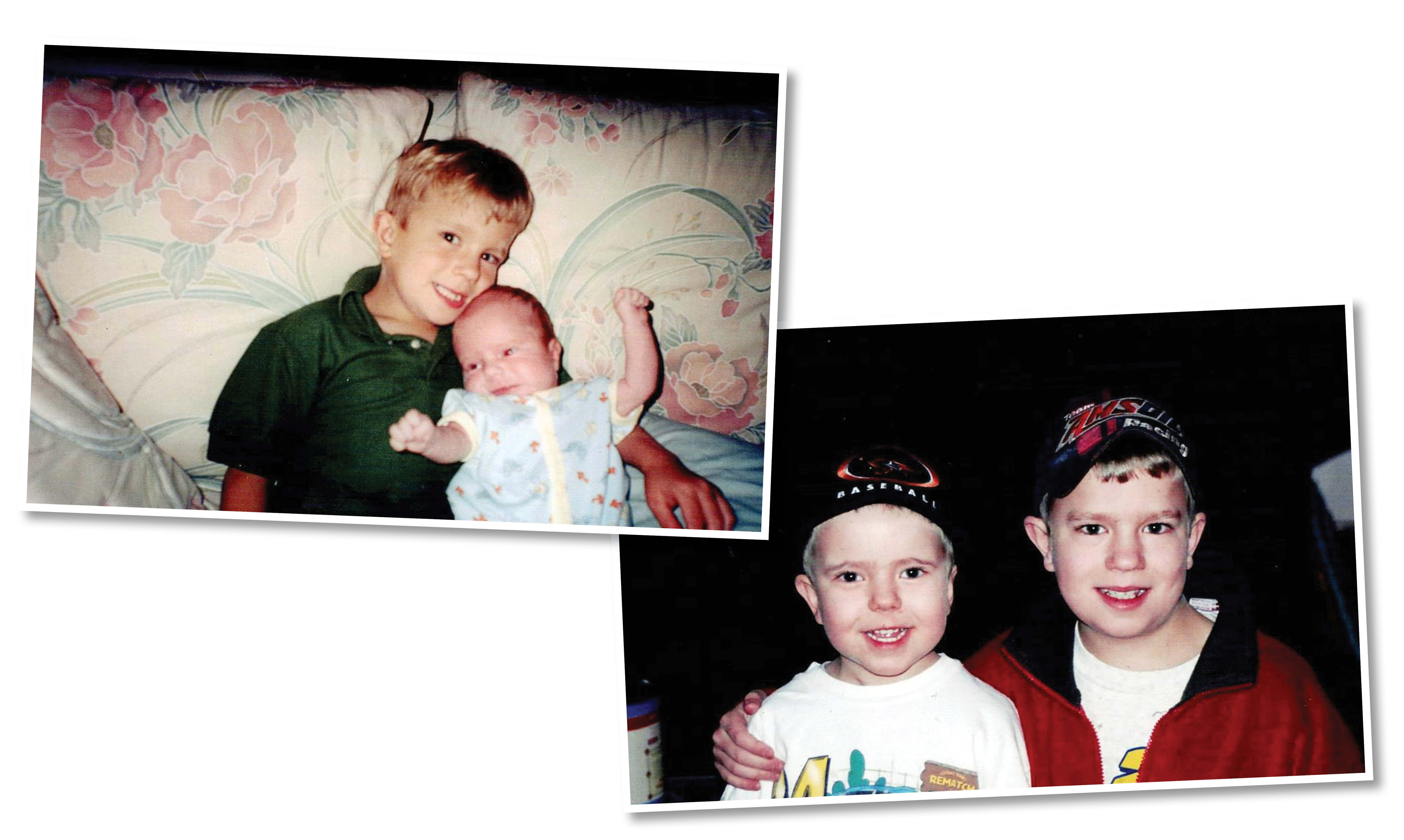

Brothers Tyler, left, and Jeremy Harshman, have been "regulars" at Johns Hopkins since they were born.

Photos courtesy of Jeanine Harshman, Mike Ciesielski

Jeanine Harshman’s pregnancy with her first son, Tyler, “could not have been more normal,” she remembers. But when Tyler was born on a Tuesday in 1992 at a hospital in Hagerstown, Maryland, he was quickly whisked away by ambulance to The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Doctors there found that his heart had just a single ventricle, compared to two of these pumping chambers in a normal heart. His brother, Jeremy, born at Johns Hopkins eight years later, was diagnosed during one of Jeanine’s prenatal visits with a different congenital heart defect (CHD) called transposition of the great arteries.

Now ages 31 and 23, and with six open-heart surgeries between the two of them, Tyler and Jeremy have received care over their entire lives at Johns Hopkins’ Blalock-Taussig-Thomas Pediatric and Congenital Heart Center — one of relatively few places of its kind that treat patients with CHDs across the life spectrum.

“There’s a significant advantage to having pediatric and adult care all in one place — to having experts who can provide care for both congenital heart disease and adult-related problems, and who know the ways in which those two worlds will interact in the same patient,” says pediatric interventional cardiologist John Thomson.

For example, general adult cardiologists typically have great depth of experience in treating coronary vascular disease and other heart problems that occur with aging but very limited training in congenital heart defects that exist since birth — and they are generally unfamiliar with the ways that early repairs deteriorate over time.

Thomson loves the extended relationships that come with his role. “We join families in their medical journey very early on, usually when patients are infants or even in utero. Then we get to know patients and their families so well, and they get to know us, as we care for them throughout the whole of their lives,” he says. “It’s extremely satisfying.”

“We get to know patients and their families so well, and they get to know us, as we care for them throughout the whole of their lives.”

John Thomson

A ‘Second Home’

Tyler Harshman, left, with baby brother Jeremy.

Tyler Harshman, left, with baby brother Jeremy.Growing up, Jeremy, left, and Tyler stayed active playing sports and riding go-karts.

Tyler’s first memories of his heart condition start at his second surgery, at nearly 6 years old, and his awareness intensified when Jeremy was born with a congenital heart defect two years later. These conditions didn’t stop their parents from letting them be typical kids — after Tyler turned 13 and Jeremy turned 8, they began racing go-karts with “the very best safety equipment we could get,” Tyler recalls. Their childhood was marked with races and learning how to build engines and make parts, a passion they have spun into a family business doing the same for sprint racecars with their father, Randy Harshman. It was also punctuated by frequent trips to Johns Hopkins Children’s Center — their medical home for their congenital heart defects since birth.

About 40,000 babies are born with congenital heart defects in the U.S. every year, affecting about 1% of all births in this country, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These defects span a wide range of types, explains Johns Hopkins’ Ari Cedars, adult congenital cardiologist for the Harshman brothers.

While Jeremy’s transposition of the great arteries is relatively common among patients with CHD, affecting about one in every 3,413 live births, Tyler’s single-ventricle defect is relatively rare, affecting only one in 20,000 live births.

Like many patients with CHDs, both brothers required urgent surgery early in life — Tyler had his first operation at about 6 months of age, and Jeremy’s first operation was at just 5 days old. A common misconception is that these initial surgeries are curative, but many congenital heart defects require multistage surgeries at different points in life, and these surgical fixes tend to deteriorate in predictable ways that require revisions over time, Cedars explains. For this reason, nearly all patients with congenital heart defects require lifelong follow-up, with most patients in the Blalock-Taussig-Thomas Center seen at least once a year.

“These frequent visits allow us to screen for and anticipate problems, and to prevent more severe problems [that could arise] if not attended to in a timely fashion,” Cedars says.

Coming to the same medical team over the long haul has a multitude of benefits for patients and their care team, Cedars adds: Clinicians forge strong relationships with young patients as they grow, gathering information on life circumstances and events that could ultimately affect heart health but might not make it onto a medical chart. For patients and families, it is reassuring to receive care in the same familiar environment by clinicians who become more like family as the years go by.

Until recently, Tyler and Jeremy usually attended their annual appointments together, accompanied by Jeanine — first with cardiologist Joel Brenner, and then with Cedars after Brenner’s retirement in 2022. The family developed its own routine over the years, visiting the Christus Consolator statue in the lobby of the Billings Administration Building before each appointment at the Blalock-Taussig-Thomas Center, now located in The Charlotte R. Bloomberg Children’s Center building.

“Johns Hopkins feels more like a second home to me than a hospital. I have always felt comfortable there,” says Jeremy.

“These frequent visits allow us to screen for and anticipate problems, and to prevent more severe problems [that could arise] if not attended to in a timely fashion.”

Ari Cedars

‘Warm’ Handoffs

These annual visits, with more interspersed as needed for check-ins and procedures, allowed the care team for Tyler and Jeremy to decide when to schedule each of them for surgery over the years to keep their hearts working well. Tyler’s first two surgeries rerouted his blood vessels in order to access oxygen-rich blood from the lungs to allow his single ventricle to pump it throughout his body. A necessary revision at age 16 replaced an artificial vein integrated during those earlier surgeries with a larger one to accommodate his growing blood vessels. Jeremy’s surgery in his first days of life switched the position of the two largest arteries leaving the heart.

Each of these surgeries, performed by longtime Johns Hopkins cardiothoracic surgeon Duke Cameron, took place before the boys turned 18. As Tyler approached this critical milestone into adulthood, Jeanine says she became nervous about the upcoming transition from pediatric to adult care — after all, Tyler, who also has type 1 diabetes, had to leave his pediatric endocrinologist behind once he became a legal adult.

But the story was different in the Blalock-Taussig-Thomas Center, she says. “The team told us that these boys were theirs forever, that they would stay with a team at the same center. It was a huge relief,” Jeanine remembers.

Indeed, says Cedars, although he is an adult cardiologist, his office sits within the Children’s Center. He says that physical location facilitates “warm handoffs” when patients with congenital heart disease age out of pediatric care, allowing pediatric colleagues to stop by to brief him on patients new to him and their often-complex histories.

The same CHD surgeons at the Blalock-Taussig-Thomas Center operate on babies and adults alike, says Danielle Gottlieb Sen, who performed Tyler’s most recent surgery in October 2023 — an operation to implant a pacemaker, since an evaluation by Cedars showed that Tyler’s heart was no longer responding to increased demand, stubbornly stuck at a heart rate of 51 beats per minute regardless of Tyler’s activity level. There are only a few hundred cardiac surgeons trained to perform surgeries for CHD over the lifespan in the U.S., with Gottlieb Sen one of just 22 women surgeons. The training for this field is the longest in all of medicine, she explains, taking on average 17 to 18 years, with more time for surgeons who pursue research concurrently, as she did.

“Congenital heart defects are more of a calling for me than a job,” she says.

Gottlieb Sen says that the training she and her colleagues received, as well as the care they provide, is vastly different from that of general cardiac surgeons who operate on patients with acquired heart disease, such as the coronary artery disease so prevalent in adults in the United States. Rather than treating conditions that arise in a structurally normal heart, she and her colleagues have the daunting task of trying to correct abnormal anatomy, often developing creative solutions customized to patients’ individual needs.

“Patients with acquired heart disease have had some time when their cardiac anatomy and function was normal. But patients with CHD have never had a normal heart. Our job is to help them live as normally as possible,” she says.

“Congenital heart defects are more of a calling for me than a job.”

Danielle Gottlieb Sen

Taking Life in Stride

To accomplish this goal, members of the congenital heart disease care team — including cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, cardiac catheterization specialists, electrophysiologists, social workers, psychologists and nurses, among others — meet every Thursday at 7 a.m. to discuss the most complex patients currently on the roster. Together, Gottlieb Sen explains, the team uses their diverse expertise to decide on the care plan for each one.

For young adults like Tyler and Jeremy, the team also helps patients transition from having their care managed by their parents and pediatric clinicians to managing their own care independently.

Today, rather than Tyler and Jeremy attending appointments jointly as they typically did in the past, Tyler — who is recently married — now often attends with his wife, Kara, while Jeremy often continues to attend with Jeanine.

With the support of their care team, both brothers have made tremendous strides both medically and personally over the years. Today, their business building racecar engines and parts is thriving. Both are active in their churches, families and communities, which they expect to continue for decades to come.

“You learn to take it in stride and go to into each appointment saying that you don’t know what will happen, but it will be OK,” says Jeanine. “We are so grateful to have had Johns Hopkins with us the whole way.”