Pediatric Oncology

Helping Our Youngest Cancer Patients

There was a TV commercial in the 1970s that showed an empty football stadium. The empty seats symbolized the astonishing number of children killed by leukemia each year in the U.S.

Very few children survived cancer during this time. There were no drug therapies. Surgeons could cut out tumors that occurred in and around organs, but if the tumor came back after surgery, there was little to offer. It was worse still for young patients suffering from cancers that formed in the blood, including leukemia, the most common childhood cancer. The disease was almost always fatal.

LEVENTHAL

LEVENTHALBrigid Leventhal

This was the scenario in which Brigid Leventhal, a Harvard Medical School graduate and National Institutes of Health-trained researcher, was recruited to Johns Hopkins in 1976 as the Cancer Center’s first pediatric oncologist and director of pediatric oncology.

Under Leventhal’s leadership, the Kimmel Cancer Center started to change the landscape of pediatric cancer research and treatment.

“Brigid Leventhal was a master clinical researcher,” says Donald Small, M.D., Ph.D., current director of pediatric oncology. Her laboratory research focused on drug therapies to treat leukemia and lymphoma and paved the way for the first clinical studies of drug therapies in pediatric cancers.

She developed a fellowship program to develop the specialty knowledge that was needed to advance the field. She was also a founding member of the Pediatric Oncology Group, one of two U.S. cooperative groups leading research against pediatric cancers.

“Fortunately, pediatric cancers are rare,” explains Small, “and early on, pediatric oncologists realized they had to band together in groups to treat patients with the same cancers in the same way to find the treatments that would improve cure rates.”

Leventhal and colleagues began treating pediatric cancers with drug therapies, first single agents and later with combinations of drugs. They began to see the first cures.

“Before chemotherapy, there were few survivors,” says Small. “Survival was measured in weeks to months.”

With chemotherapy came toxicities, and Leventhal also led the way in recognizing and managing the impact of early drug therapies on young patients with cancer.

“Beyond the aura of risk always hanging over them, they face huge difficulties getting good jobs, breaking into careers and getting insured. The drugs produced wide swings of mood and unlovely behavior for which they blamed themselves. Family and friends and teachers don't always understand. Even physicians expected patients to be grateful they were alive. Many viewed demands for more of the good life, friends, college education, insurance, careers, marriage and kids as greedy, and if appropriate at all, it must at least be way down on the list of priorities,” said Leventhal in 1986.

Patients disagreed, and so did Leventhal, becoming one of the first to lead the charge for scaled back therapies when possible and management of treatment side effects.

Most pediatric oncologists shied away from taking on this challenge. Leventhal was undeterred. She began a pioneering study of Hodgkin lymphoma, which led to refinements in therapy that allowed certain patients, based on specific characteristics, to receive less radiation or forgo it all together without increased risk of recurrence.

WHARAM

WHARAMShe worked closely with radiation oncologist Moody Wharam. He developed the standard of care for a pediatric cancer of the connective tissue that attaches muscles to bone, called rhabdomyosarcoma. Working with the Pediatric Oncology Group, he developed a chemotherapy/radiation therapy combination that led to improved survival and that remains the foundation for how children with this cancer are managed today. It also earned the Center’s radiation oncology program distinction as one of just a select few in the nation with expertise in treating pediatric patients with cancer.

Curt Civin

CIVIN

CIVINThese refinements in cancer therapy continued. In 1984, when Leventhal stepped down and Curt Civin, M.D., took over as director of pediatric oncology, he began taking a closer look at the treatment for acute lymphocytic leukemia, the most common cancer in children.

Chemotherapy had made dramatic improvements, but still only half of patients diagnosed survived. By reclassifying the subtypes and changing the way chemotherapy was administered, Civin dramatically improved survival rates to nearly 90%.

Civin also expanded the pediatric oncology program to six faculty members. In addition to providing clinical care to patients, he required all faculty members to conduct laboratory research, earning the pediatric oncology program a reputation as a translational research powerhouse. He earned a training grant from the National Institutes of Health to support this in-depth training in laboratory research.

This bench-to-bedside approach was aimed at improving survival among patients with pediatric cancers.

“We’re specialists. We take the toughest cases — the patients that others cannot help — and give them a chance,” said Civin in 1995. “When I became a pediatric oncologist, just 30% of patients were cured, and a few decades later that improved to 70%. I am proud to say that Johns Hopkins has played an instrumental role in changing these statistics.”

Civin’s laboratory research focused on leukemia and was aimed at understanding what went wrong in the development of blood cells that leads to cancer. Research into blood-forming cancers at the time was limited because of the inability to isolate and study blood stem cells. These cells reside in the bone marrow and make up just 1% of bone marrow cells, but they are critically important because they give rise to every other type of blood cell.

It is in these cells, Civin theorized, that something went awry, causing unchecked growth of one type of cell at the expense of all other blood cells.

After two decades of tracking the elusive blood stem cells, Civin developed the CD34 antibody, which worked as a literal stem cell magnet, picking out these rare cells. The breakthrough made it possible to transplant healthy stem cells into people with cancer to help repopulate a patient’s blood and immune system after treatment to destroy cancer cells. It also provided a better understanding of how leukemia and lymphoma originated.

The use of the CD34 antibody was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1996, and since that time, thousands of patients have been treated worldwide using Civin’s technology.

Michael Kastan

KASTAN

KASTANAnother pediatric oncologist, Michael Kastan, M.D., Ph.D., was also leading pioneering research as he determined the function of the p53 gene, the most commonly altered gene in cancer.

Kastan identified the biochemical pathway of the P53 gene, and found that this gene causes damaged cells to stop reproducing. When this gene is missing or mutated, damaged cells grow unchecked, potentially resulting in cancer.

Although chemotherapy and radiation resulted in significantly improved survival rates, researchers noted that some cancers grew resistant to the treatments. Kastan began studying the cellular and genetic responses to chemotherapy and radiation, which work by damaging tumor cell DNA. This damage results in a sequence of intracellular events that lead to cell death, but in some cases, rather than dying, the tumor cells keep growing or temporarily stop growing for a time and then start growing again.

The signal for cells to die after DNA damage caused by radiation or chemotherapy works through the P53 tumor suppressor gene, he found. Researchers in the Kastan lab discovered that certain growth factors can also play a role in the cell’s decision to live or die. If the growth factor is present or if the tumor cell contains cellular molecules that are usually stimulated by the growth factors, the tumor cell is better able to survive cancer therapy.

This research led to some of the first studies in targeted therapies — drugs that block these signals that drive cancers to grow and spread.

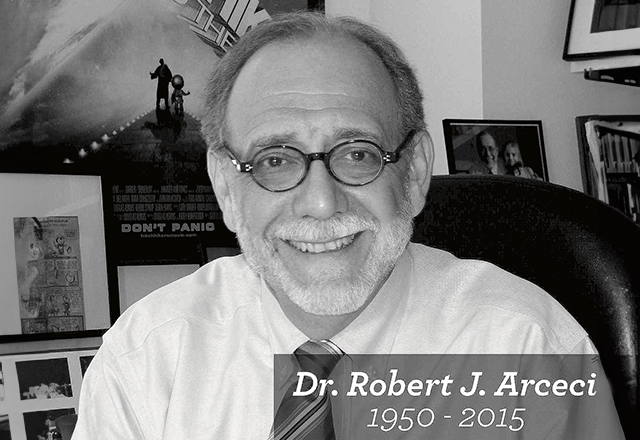

Robert Arceci

ARCECI 1950-2015

ARCECI 1950-2015Robert Arceci, M.D., Ph.D., followed Civin as director of pediatric oncology and continued to build the strength of the Center’s research and patient care. He increased the number of faculty members to 10 and led research of acute myeloid leukemia in the Children’s Oncology Group, helping identify molecular targets that led to improvements in therapy in pediatric and adult patients.

Arceci also worked with the Histiocytosis Society, and helped uncover mutations linked to histiocytosis, a cancer-like disease characterized by abnormally increased numbers of a type of white blood cell called histiocytes. The disease had been largely considered a mystery until Arceci helped identify the mutations.

Describing what drove him to focus his career on pediatric cancers, Arceci said, “Children are going to be the people who help the adults. They are going to save us. I think it is truly phenomenal.”

Donald Small

Arceci’s work on the AML committee of the Children’s Oncology Group also helped advance the research of Donald Small, M.D., Ph.D., the Kyle Haydock Professor and Director of Pediatric Oncology.

SMALL

SMALLSmall worked with and says he was impacted by all of his predecessors. He was a trainee under Leventhal and a young, new faculty member under Civin, working in his laboratory to better understand how blood cells grow and expand.

The research he began in Civin’s laboratory ultimately led to a pioneering discovery in a type of leukemia called acute myeloid leukemia. He cloned a gene called FLT-3 and linked it to poor survival for patients with this cancer.

“Having an FLT-3 mutation reduces the chances of curing an AML from about 50% to less than 20%,” says Small.

Small identified a drug to target FLT-3 and worked with Kimmel Cancer Center colleague Mark Levis, M.D., Ph.D., to develop a test to tell if the drug was hitting its FLT-3 target.

With Arceci’s encouragement, Small headed the AML committee of the Children’s Oncology Group for five years, and this later helped him to bring FLT-3 inhibitors to clinical trials in pediatric patients.

Better iterations of FLT-3 inhibitors are now being studied alone and combined with other drugs for the treatment of AML in adults and children.

Small also grew the pediatric oncology program to 21 faculty members and developed subspecialties in sarcoma, neuro-oncology, leukemia and lymphoma, and bone marrow transplant.

Under his leadership, the joint pediatric oncology fellowship between the National Institutes of Health and the Kimmel Cancer Center was established to improve training. Three to six fellows go through the program each year, training four months at the National Institutes of Health and seven months at the Kimmel Cancer Center.

He also a launched an annual lecture honoring pediatric oncology founder Brigid Leventhal, and notes that today, half of pediatric oncology faculty members are female.

Leventhal was a strong advocate for pediatric oncology patients, believing they did not get enough support after treatment. Small continues to strengthen programs that aid pediatric patients with cancer, including its long-term survivors program — one of the first childhood cancer survivors programs in the country to study, monitor, treat and develop methods to prevent and address long-term complications of cancer therapy.

“When you think that just a couple decades ago, few children survived a diagnosis of cancer, and that today, the reverse is true, you realize the power of research and the kind of change it can bring,” says Small. “This kind of translational research is the hallmark of our Cancer Center.”

Pediatric Oncology Advances

A State-of-the-Art Hospital

The Charlotte R. Bloomberg Children’s Center, a technologically advanced but patient- and family-friendly building, is home to our pediatric oncology inpatient unit and outpatient clinic. The inpatient unit and outpatient clinic are located on the 11th floor. The state-of-the-art Children’s Center inpatient unit has 20 private rooms with the ability to expand to 22. It includes a playroom for children and a separate room for teenagers, and a host of amenities for the comfort of families, including sleeper sofas in every room, lounges, showers, laundry facilities and 24-hour food service. The outpatient unit has eight exam rooms for private infusion areas and a beautiful, two-story open infusion area with five additional chairs and beds. It has two waiting areas separately and distinctively designed for the different interests and needs of children and teenagers, and also has an on-floor pharmacy.

The Forgotten Demographic

A study published in 2008 found that 16- to 20-year-olds with acute lymphocytic leukemia, a cancer that occurs in children and adults, who receive pediatric care had nearly 20% higher survival rates than those who received adult care.

“Overall cure rates among pediatric cancer patients are 50% higher than the rates among adult cancers,” says Donald Small, M.D., Ph.D., Kyle Haydock Professor and Director of Pediatric Oncology. “It makes a lot of sense. An adolescent’s or young adult’s organ systems are more like a 10-year-old than a 65-year-old. The therapy that we give is more intense, but it turns out that young adults can tolerate that, and as a result, cure rates are higher.”

This realization inspired Johns Hopkins Hospital leadership, in 2019, to raise the cutoff age of patients who could be treated in pediatric oncology from 21 to 25.

“The new age can be modified, leaving plenty of room for pediatricians and adult doctors to work together and recommend patients to each other,” says Kenneth Cooke, M.D., the Herman and Walter Samuelson Professor of Oncology and head of the pediatric oncology blood and bone marrow transplantation program. “We are all under one roof at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, which gives our patients an important advantage, but there’s still work to be done to ensure that each patient gets the correct treatment regardless of age.”

He points out that there are some cancers that occur in pediatric and adult patients but are more common among children, teens and young adults. In these cases, age cutoffs for treatment can be arbitrary and even detrimental. Doctors may refer a 17-year-old diagnosed with cancer to a pediatric oncologist, but another patient with a few months’ difference in age and with the same diagnosis might be sent to an adult oncologist, says Cooke, who treats children, teens and young adults up to their late 20s.

Kimmel Cancer Center pediatric oncologists and nurses find most teens and young adult patients prefer the pediatric setting, which offers more one-on-one care and generally provides more logistical and emotional support than adult units.

The Story of Camp Sunrise

What began in 1987 with seven campers has grown into the Kimmel Cancer Center-maintained and operated Camp Sunrise, with more than 100 campers and 70 trained volunteers and medical staff members. For one week each summer, campers and volunteers come together at Elks Camp Barrett in Crownsville, Maryland, for hiking, swimming, dancing, crafts, games, sports, campfires and reunions with friends.

Camp Sunrise may be the only place where cancer takes a backseat to childhood and teenage fun. The goal of the camp is to give campers the best week of their lives. Beyond the fun, campers treasure the direct connection to other kids who understand and share their unique experience.

Camp Sunrise is for former and current cancer patients who are 4 to 18 years old. The 4- and 5-year-olds participate in a day camp, and campers 6 to 16 years old come for a traditional residential sleepover camp, complete with rustic cabins and plenty of outdoor adventures. The older, 17- and 18-year-old campers take part in a leadership training program so, if they choose, they may join the ranks of the Camp Sunrise volunteers as camp counselors.

At the end of camp each year, the entire group of campers and volunteers gather to plant a tree and decorate it with handmade ornaments that honor their journeys as cancer patients and survivors. Year after year, as campers return, they see these trees — like their friendships — grow in number and strength.

About one-quarter of the campers are actively being treated for cancer when they come to camp. They rely on the Kimmel Cancer Center physicians, nurses and physician assistants who care for them in the medical room campers have dubbed the “Funny Farm.” A member of the medical team is on hand 24 hours a day to administer chemotherapy, draw blood for lab work and provide any other care needed. Campers also come to the Funny Farm for care of camp-related bumps, scrapes and bruises.

For most kids, a cancer diagnosis makes summer camp an impossibility. It becomes one more thing that makes them different from others their age. At Camp Sunrise, cancer doesn’t call the shots. Prostheses are hung behind doors on coat hooks, wigs and scarves are often put aside in favor of bald heads, and no explanations are necessary. Everyone fits in, and everyone there — campers, counselors and volunteers — understands.

Children with Cancer and Other Special Needs Deserve Support During Online Learning

Thousands of schools transitioned to online learning in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, during which time many children with cancer and other chronic health needs, as well as those with special education needs, faced significant challenges to learning online.

Children undergoing cancer treatment may have symptoms such as fatigue, pain, motor impairments or vision/hearing loss that make learning more challenging, says Kathy Ruble, Ph.D., M.S.N., R.N., C.R.N.P., director of the pediatric oncology survivorship clinic at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center. Additionally, therapy frequently induces deficits in attention, executive function, processing speed, behavior regulation and overall IQ.

“There are many departments within the health care system that can help with disease-acquired or treatment-acquired disabilities that I think we underutilize because we don’t think about it enough,” says Ruble.

She and her team developed a continuing medical education course on the Coursera platform. Kids with Cancer Still Need School: The Providers Role helps oncology health care providers navigate the challenges associated with the neurocognitive impacts of therapy.

Ruble is also co-founder of the SUCCESS (Supporting and Understanding Childhood Cancer: Education, Strategies, and Services) lab at Johns Hopkins, which works with families of children with cancer and pediatric oncology teams to find better ways to help survivors thrive in school.Children undergoing cancer treatment may have symptoms such as fatigue, pain, motor impairments or vision/hearing loss that make learning more challenging, says co-author Kathy Ruble, Ph.D., M.S.N., R.N., C.R.N.P., director of the pediatric oncology survivorship clinic at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and School of Nursing. Additionally, therapy frequently induces deficits in attention, executive function, processing speed, behavior regulation and overall IQ.Although clinicians in pediatric oncology or other subspecialties are the ones who spend the most time with families, they’re often the least well-equipped to handle these types of issues, Ruble says.“If somebody is having difficulty walking, we don’t have any problem sending them to physical therapy,” she says. “But if someone can’t hold their pen, or employ fine motor skills to use the computer, we’re much less likely to pick that up in a clinical visit and send them to occupational therapy. There are many departments within the health care system that can help with disease-acquired or treatment-acquired disabilities that I think we underutilize because we don’t think about it enough.”Patients and family caregivers should bring up concerns to every clinician they encounter and ask for assistance, she advises. Meanwhile, she says, during examinations clinicians should ask about school performance, look for signs and symptoms that might make learning challenging, and learn what resources are available within their institutions or communities. Pediatric neuropsychology teams, social workers and disease-specific organizations may also be helpful.

In addition, Ruble and her team developed a continuing medical education course to help oncology health care providers navigate the challenges associated with the neurocognitive impacts of therapy. It is available as a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC), free online courses open to anyone, on the Coursera platform Kids with Cancer Still Need School: The Providers Role.

Ruble is co-founder of the SUCCESS (Supporting and Understanding Childhood Cancer: Education, Strategies, and Services) lab at Johns Hopkins, which works with families of children with cancer and pediatric oncology teams to find better ways to help survivors thrive in school. It has received funding through three engagement awards from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. For more information, see Childhood Cancer Survivors May Face Neurocognitive Challenges. Johns Hopkins’ SUCCESS Lab Works to Ensure They Receive a Quality Education.

Help Along the Way

Pediatric oncology patient care and research has been advanced by a number of generous donors:

Ginny and Fred Mitchell established the Pediatric Oncology Friends in 1994 after losing their son to cancer. The group raised more than $1 million for pediatric oncology research at the Kimmel Cancer Center.

Children’s Cancer Foundation funded a variety of programs and discoveries, donating more than $8 million for pediatric cancer research and facilities at Johns Hopkins since 1979. Donations supported renovations to the pediatric oncology outpatient and inpatient units, the pediatric bone marrow transplant center, the clinical research of pediatric neuro-oncologist Kenneth Cohen, M.D., and the leukemia research of Donald Small, M.D., Ph.D., and Alan Friedman, M.D.

Giant Food’s annual campaign has provided more than $1 million each year over the past 19 years to pediatric oncology. Challice Bonifant, M.D., Ph.D., is a current recipient with funding to support her research of stem cell transplantation for high-risk leukemia and the development of immune therapies.

Hyundai Hope on Wheels has donated more than $2.8 million to the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center for pediatric oncology research. The latest recipient was Micah Maxwell, M.D., Ph.D.

Optimist International established an endowed research fellowship grant and innovation fund, providing the largest support ever by a youth-focused community service organization. Optimist fellows have included Emi Caywood, M.D., for retinoblastoma research, Eric Schaffer, M.D., for leukemia research, Brian Ladle, M.D., for immunotherapy research, Sama Ahsan, M.D., for glioma brain cancer research, and Cara Rabik, M.D., Ph.D., for leukemia research.

For Clinicians Clinical Connection

Clinicians, discover the latest in research and clinical innovation from Johns Hopkins experts. Access educational videos, articles, CME courses and other resources from our world-renowned institution.