Building A Cancer Center The Early Years

The Early Years

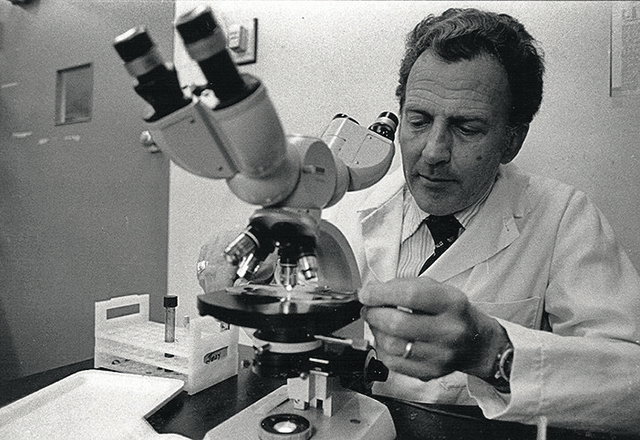

Owens Jr.

Owens Jr.In 1968, with a pH meter and a card table as his primary tools, a young doctor named Albert Owens Jr. was launching the field of oncology, and at the same time, advocating for a hospital at Johns Hopkins focused solely on the research and treatment of cancer. It was an entirely novel idea.

Despite the rising incidence of cancer in the U.S. — nearly 1 million people a year diagnosed and the number climbing — and a daunting lack of solutions to address the growing health concern, Owens faced tremendous opposition. A hospital built around this group of diseases called cancer represented a paradigm shift, and one much of the medical community did not embrace.

“Prior to the 1960s, oncology as a field of study or clinical specialty was not represented in the vast majority of academical medical centers. In most hospitals, including Johns Hopkins, patients were cared for by a wide variety of clinicians — very few with a special interest or competence in oncology. The means of effecting the course of this relentless disease were very limited, and most patients presented with advanced disease,” Owens reflected in 1998.

During the 1960s, a handful of pioneering doctors and researchers at Johns Hopkins espoused a different vision and became academic leaders in the field. Our nurses became leaders in the development of oncology nursing as a recognized specialty, and our Patient and Family Services also earned wide recognition. Owens believed that the group he assembled could change the trajectory of cancer.

“Cancer is a challenging scientific and social problem of great magnitude. Science will show us the way to control these diseases. Addressing a major social problem, I would say, is a quite proper pursuit for any university,” he told Johns Hopkins University leadership.

Santos

SantosIn 1973, the trustees of the university and hospital approved the construction of the Johns Hopkins Oncology Center. The Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins was one of the first approved under the National Cancer Act of 1970, and it quickly earned comprehensive cancer center status and recognition as a Center of Excellence.

Owens’ vision was to bring together the best and brightest physicians from across the country. His first recruit was Navy officer George Santos, who was performing some of the earliest research of bone marrow transplantation for leukemia. Next, he hired pharmacologist Michael Colvin, who was already studying cancer-fighting drugs at the National Cancer Institute.

What we will accomplish today is certain to be a pale representation of what is to come."

Albert Owens, Jr 1977

Wharam

WharamOthers followed, including Paula Pitha and Nancy and Joel Shaper, who were studying the association between viruses and cancer; leukemia experts Phil Burke and Judy Karp; Brigid Leventhal, a pediatric oncologist, who was heading the fight for cancer’s youngest victims; Moody Wharam, Stanley Order and Eva Zinreich, who were building a radiation oncology program; and Linda Arenth and Connie Ziegfeld, who developed our nursing program.

Ziegfeld

ZiegfeldOwens required collaboration, and he created an environment where it flourished. He oversaw the construction of the first Cancer Center building, which opened in 1977, and had research laboratories located adjacent to inpatient units to facilitate research focused on the cancer problems clinicians observed at the bedside. Today, we call this visionary approach translational research. This close collaboration of researchers and clinicians became a hallmark of the Cancer Center.

“From that day on, our mission was to promote research and education in cancer and related disorders with a focus on human disease. We are bound by this mission to provide specialized patient treatment reflecting the latest scientific and technological achievements and develop effective methods of disease detection and prevention,” said Owens.

This early work has resulted in history-making progress against cancer.

Our researchers have made pioneering contributions in cancer genetics, epigenetics, immunology drug development, community outreach and disparities, and more, applying discoveries across cancer types to facilitate new cancer prevention and detection strategies and therapies.

Designating Maryland's BMT Program (1977)

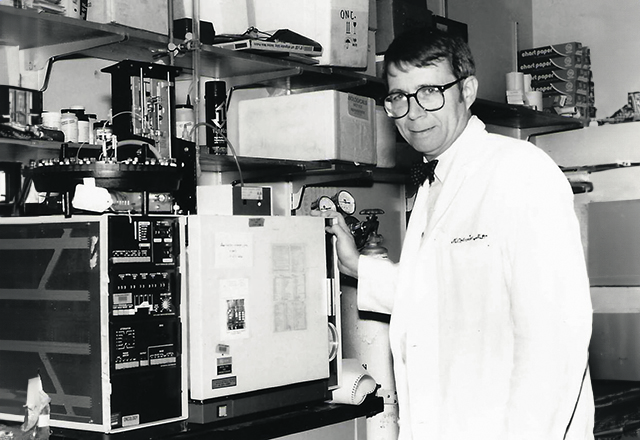

Designating Maryland's BMT Program (1977) Michael Colvin

Michael ColvinThese discoveries informed the genetic and epigenetic landscape of cancer, revealed PD-L1 expression and mismatch repair deficiency as a biomarker for response to immunotherapy, and inspired the development of new therapeutics, such as cancer cell metabolism-targeting drugs, POL-1 inhibitors, FLT3 inhibitors and bispecific antibodies. Our experts led studies that resulted in historic FDA approvals of new cancer drugs.

Although the growth of our clinical and laboratory research led to separate research and clinical buildings, the original translational mission of interdisciplinary collaboration continues, as is reflected by the breadth of these initiatives and collaborations throughout The Johns Hopkins University.

The work of our Cancer Center has lived up to Owens’ 1977 prediction. He said, “What we will accomplish today is certain to be a pale representation of what is to come.”

The Early Years

Timed Sequential Therapy

Leukemia expert Philip Burke developed Time Sequential Therapy, using short courses of high-dose anticancer drugs specifically timed to be given when cancer cells were reproducing and more sensitive to drug therapy. His treatment resulted in remissions in 70% of patients with leukemia who were treated.

High-Risk Screening

Our Breast and Ovarian Surveillance Service, run by nurse Patti Wilcox, for women with a family history of breast cancer or ovarian cancer, and Polyposis Clinic, run by nurse Susan Booker, for those at increased risk for colon cancer, were implemented when screening programs were in their infancy. These served as national models, and were instrumental in facilitating prevention, early detection and early treatment.

The Nuclear Matrix

Abnormalities in the shape of the cancer cell nucleus are a hallmark of cancer diagnosis. Donald Coffey discovered that a superstructure within the cell, which he named the nuclear matrix, was responsible for the misshaped nucleus. The nuclear matrix, he and his research team learned, was the site for DNA replication and shed the first light on the cellular changes that caused normal cells to turn into cancer cells.

Hemapheresis

The Center’s hemapheresis program began as a second-year fellowship project of senior faculty member Hayden Braine to provide white cell support to patients suffering infections. Later, it provided platelet support to patients undergoing chemotherapy, bone marrow processing and purification, as well as administration of an unrelated bone marrow donor registry.

The Cancer Information Service

The Johns Hopkins Cancer Information Service (CIS), opened in 1976 and headed by Donna Cox, responded to telephone inquiries from patients, families, health professionals and the public. Our CIS was contracted by the National Cancer Institute to provide information on cancer clinical trials, treatment centers, the latest cancer research and more.

Anticipatory Nausea

Nausea and vomiting after chemotherapy were common side effects of cancer treatment, but some patients developed these symptoms before receiving treatment. Termed anticipatory nausea and vomiting, symptoms were triggered by treatment-related stimuli, such as intravenous needles and clinic odors. Anticipatory symptoms most commonly occurred in patients who suffered post-chemotherapy nausea and vomiting. Medical oncologists John Fetting and Stephen Staal conducted a study to uncover the mechanisms causing the anticipatory symptoms and to study the drug clonidine for its ability to target the mechanism and reduce symptoms.