Pain is complicated, Jennifer Haythornthwaite tells her first-year medical students.

“No two people experience pain the same way,” she says. “We can give hundreds of people the same stimulus and each person’s going to have a different response.”

Haythornthwaite teaches the Pain Care Medicine course that’s required for all first-year Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine students. During four days of instruction, students hear from Johns Hopkins patients, surgeons, pharmacists, physical therapists and nurses. Haythornthwaite, a psychologist, discusses psychosocial issues such as poor sleep and depression, which can result from pain and also make pain worse.

“They leave understanding that pain management is more than just prescribing opioids,” she says. It could involve physical therapy, counseling or nonnarcotic medications, for example.

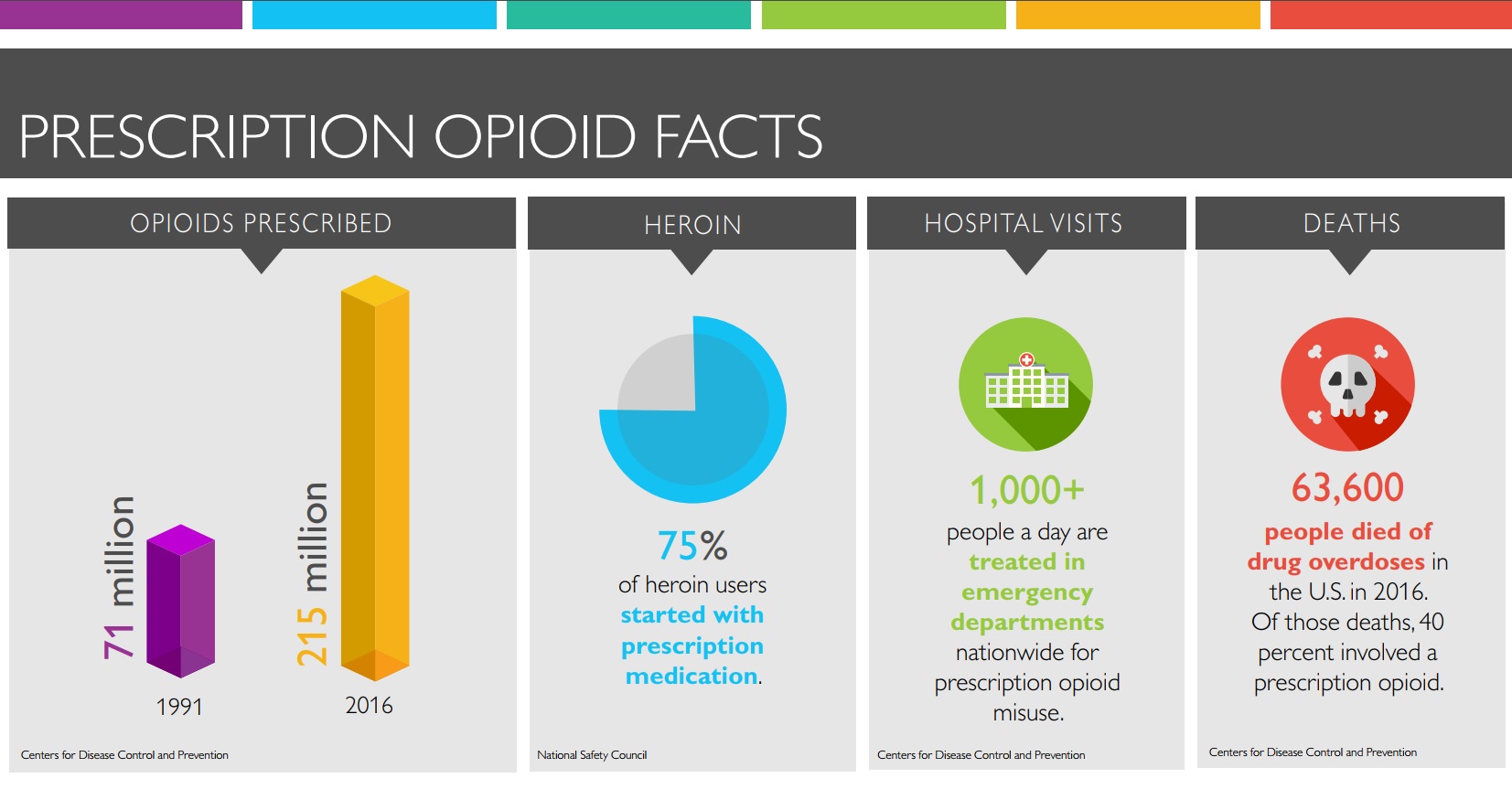

The class was developed in 2010 by neurologist Beth Hogans. At the time, she says, only about 10 percent of medical schools nationwide offered pain management training. As opioid overdoses and deaths escalated, more added courses that help doctors in all specialties understand and treat pain while minimizing opioid prescribing.

“Our whole program is geared to teaching students the hazards of opioids and the fact that pain should be addressed comprehensively,” says Hogans. “Opioids seem easy — give a prescription and the pain will go away. They have a time and place, but even a short course of opioids can lead to fatal abuse. And the more you’re exposed to them, the less your body responds.”

Prior to pain management education, many doctors believed that opioids carried few risks — thanks, in part, to a widely circulated claim printed in the New England Journal of Medicine in January 1980.

Under the heading Addiction Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics, a doctor and assistant at Boston University Medical Center reported that just four out of nearly 12,000 patients treated with narcotics had formed addictions. It was a letter, not a study, and it referred to hospitalized patients and not ones who were discharged after surgeries. But in the following decades, the brief write-up was cited over and over again as proof that opioids were not addictive.

Meanwhile, doctors were being encouraged to take patient pain more seriously. In 1995, James Campbell, then director of the Blaustein Pain Treatment Center at The Johns Hopkins Hospital and president of the American Pain Society, argued that pain should be measured as a fifth vital sign, alongside blood pressure, temperature, heart rate and respiratory rate.

Other Articles in this Series

Two years later, the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society issued a joint statement declaring “the undertreatment of pain in today’s society is not justified.” Around the same time, drug company Purdue Pharma introduced OxyContin, a potent opioid for treating severe pain. OxyContin is a slow-release drug, and the company argued, controversially, that it carried a lower risk of addiction compared to fast-acting opioids.

Family doctors and others with little education in pain management or addiction began prescribing opioids in unprecedented amounts. The medications were inexpensive and increased patient satisfaction, at least in the short term, by blunting pain. It was also easier to prescribe opioids than treatments such as physical therapy or counseling that could be difficult for patients and weren’t always covered by insurance.

Now, as the opioid epidemic takes its toll across the United States, health care leaders are advocating a more nuanced approach to pain management, one that uses prescription opioids as a last resort, encourages use of the full range of options and guides patients toward learning to live with some pain.

Education is an important part of that change.

“We prepare our students to understand that each patient is different,” says Haythornthwaite. “They have a responsibility as physicians to make sure they’re thinking comprehensively about how to treat them.”