Colostomy

What is a colostomy?

A colostomy is surgery to create an opening for the colon (large intestine) through the belly (abdomen). A colostomy may be short-term (temporary) or long-term (permanent). It's often done after bowel surgery or injury. Most permanent colostomies are end colostomies. Many temporary colostomies bring the side of the colon up to an opening in the abdomen. This is known as a loop colostomy.

During an end colostomy, the end of the colon is brought through the abdominal wall. Then it may be turned under, like a cuff. The edges of the colon are then stitched to the skin of the abdominal wall to form an opening called a stoma. Poop (stool) drains from the stoma into a bag or pouch attached to the abdomen. In a temporary loop colostomy, a hole is cut in the side of the colon and stitched to a matching hole in the abdominal wall. This can be more easily reversed later. This is done by removing the colon from the abdominal wall. Then the holes are closed so that poop flows through the colon again.

Why might I need a colostomy?

Colostomy surgery may be needed to treat several different diseases and conditions. These include:

-

Birth defect, such as a blocked or missing anal opening, called an imperforate anus

-

Complications from diverticula. These are small, bulging pouches of the colon. They are common in people older than age 60. They can become infected (diverticulitis). Or they can cause severe bleeding and need bowel surgery.

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

-

Injury to the colon or rectum

-

Partial or complete intestinal or bowel blockage

-

Rectal or colon cancer

-

Wounds or fistulas in the perineum. A fistula is an abnormal connection between internal parts of the body. Or between an internal organ and the skin. A woman's perineum is the area between the anus and vulva. In men it is between the anus and scrotum.

If surgeons have the choice to create a temporary colostomy, they often will. Talk with your healthcare provider before surgery to see if your colostomy will be permanent or temporary. Some infections or injuries require giving the downstream bowel a rest with a colostomy so that it can heal. Then it is reattached later.

In some cases, a surgeon may need to make a permanent colostomy. For instance, this may be advised if cancer is the cause and the rectum must be removed. Or if there is a failure of the rectal muscles that control pooping.

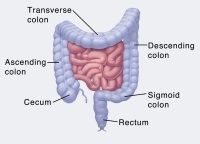

The digestive system

A colostomy won't change the way your digestive system works. Normally, after you chew and swallow your food, it goes through your esophagus, or swallowing tube, into your stomach.

From there, it travels to your small intestine and then to your large intestine, or colon. Hours or days later, the indigestible residue leaves the storage area of your rectum through your anus, as poop. Poop typically stays loose and liquid during its passage through the upper colon. There, water is absorbed from it. So the poop gets firmer as it nears the rectum.

The ascending colon goes up the right side of your body. The poop here is liquid and somewhat acidic, and it contains digestive enzymes. The transverse colon goes across your upper abdomen. And the descending and sigmoid colon go down the left side of your body to your rectum. In the left colon, the poop becomes progressively less liquid, less acidic, and contains fewer enzymes.

Where your colon is interrupted by the colostomy determines how irritating to the skin your poop output will be. The more liquid the poop, the more acidic. And the more important it will be to protect your abdominal skin after a colostomy.

What are the risks of the procedure?

Getting a colostomy marks a big change in your life, but the surgery itself is not complex. It will be done under general anesthesia, so you will be asleep and feel no pain. A colostomy may be done as open surgery, with one main cut. Or it may be done laparoscopically, with several tiny cuts.

As with any surgery, the main risks for anesthesia are breathing problems and poor reactions to medicines. A colostomy carries other surgical risks:

-

Bleeding

-

Damage to nearby organs

-

Infection

After surgery, risks include:

-

Narrowing of the colostomy opening

-

Scar tissue that causes intestinal blockage

-

Skin irritation

-

Wound opening

-

Getting a hernia at the incision

How do I get ready for a colostomy?

Before surgery, discuss your surgical and postsurgical choices with a healthcare provider and an ostomy nurse. This is a nurse who is specially trained to help colostomy patients. It may also help to meet with an ostomy visitor. This is a volunteer who has had a colostomy and can help you understand how to live with one. And, before or after your surgery, you may want to join an ostomy support group. You can find out more about such groups from the United Ostomy Associations of America or the American Cancer Society.

If the colostomy surgery is not done as an emergency procedure, your healthcare team will give you specific presurgery instructions about diet and medicines. Follow all presurgery directions and contact your healthcare provider if you have questions.

What happens during the colostomy?

Depending on why you need a colostomy, it will be made in one of four parts of the colon: ascending, transverse, descending, or sigmoid.

-

Transverse colostomy. This is done on the middle section of the colon. The stoma will be somewhere across the upper abdomen. This type of surgery is often temporary. It's typically done for diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, blockage, injury, or a birth defect. In a transverse colostomy, the poop leaves the colon through the stoma before reaching the descending colon. Your stoma may have one or two openings. One opening is for poop. The second possible stoma is for the mucus that the resting part of your colon normally keeps producing. This mucus will pass through your rectum and anus if you have only 1 stoma.

-

Ascending colostomy. This goes on the right side of your abdomen. It leaves only a short part of the colon active. It's generally done only when blockage or severe disease prevents a colostomy further along the colon.

-

Descending colostomy. This goes on the lower left side of the abdomen.

-

Sigmoid colostomy. This is the most common type. It's placed a few inches lower than a descending colostomy.

What happens after the colostomy?

You may be able to suck on ice chips on the same day as your surgery. You'll likely be given clear fluids the next day. Some people eat normally within 2 days after a colostomy.

A normal stoma is moist and pink or red colored. When you first see your colostomy, it may look dark red and swollen, with bruises. Don't worry. In a few weeks, the color will lighten and bruises should disappear.

The bandage or clear pouch covering your colostomy right after surgery likely won't be the same type that you'll use at home. Your colostomy will drain poop from your colon into this colostomy pouch or bag. Your poop will probably be more liquid than before surgery. Your poop consistency will also depend on what type of colostomy you have and how much of your colon is still active.

In the hospital

A colostomy requires a hospital stay of about 3 days to a week, depending on the reason for the colostomy. Your stay will probably be longer if the colostomy was done for an emergency. You'll learn to care for your colostomy and the appliance or pouch that collects your poop during your hospital stay.

Your nurse will show you how to clean your stoma. You'll do this gently every day with warm water only after you go home. Then gently pat dry or allow the area to air dry. Don't worry if you see a little bit of blood.

Use your time in the hospital to learn how to care for your colostomy. You will need to wear a slim, lightweight, drainable pouch at all times if you have an ascending or transverse colostomy. There are many different types of pouches. They vary in cost and are made from odor-resistant materials.

Some people with a descending or sigmoid colostomy can learn over time to predict when their bowels will move and wear a pouch only when they expect a movement. They may also be able to master a process called irrigation to stimulate regular, controlled bowel movements.

Before going home, talk with an ostomy nurse or other expert who can help you try out the equipment you'll need. What works best will depend on what type of colostomy you have, the length of your stoma, your abdominal shape and firmness, any scars or folds near the stoma, and your height and weight.

Sometimes the rectum and anus must be surgically removed, leaving what's called a posterior wound. In the hospital, you'll use dressings and pads to cover this wound. You may also take sitz baths. These are shallow, warm-water soaks. Ask your healthcare provider and nurse how to care for your posterior wound until it heals. If problems occur, contact your provider.

At home

The skin around your (pink) stoma should look like the skin on the rest of your belly. But due to exposure to poop, especially loose poop, the skin can get irritated. Here are some tips to protect your skin:

-

Make sure your pouch and skin barrier opening are the right size.

-

Change the pouch when it is about 1/3 full to prevent leakage and skin irritation. Don't wait until your skin begins to itch and burn.

-

Remove the pouching system gently, pushing your skin away instead of pulling.

-

Barrier creams may be used if the skin becomes irritated despite these measures.

Tell your healthcare provider if you have any of these:

-

Severe cramps that last more than 2 hours

-

Blocked stoma or stoma collapse

-

Excessive bleeding from the stoma or a moderate amount of blood in the pouch (Note: eating beets will lead to some red discoloration in the poop)

-

Severe injury or cut to the stoma

-

Ongoing skin irritation

-

Continuous nausea or throwing up

-

Bad or unusual odor for more than a week

-

Change in your stoma size or color

-

Blocked or bulging stoma

-

Watery poop for more than 5 hours

-

Inability to wear the pouch for 2 to 3 days without leaking

-

Anything abnormal that concerns you

A good rule is to empty your pouch when it's 1/3 to 1/2 full. And change the pouch before it leaks. Different pouching systems are made to last different lengths of time. This may be anywhere from every day to every week. Ask your healthcare team about what financial resources may be available if you need help paying for colostomy supplies.

A colostomy represents a big change. It takes some adjustment. Even though you can feel the pouch against your body, no one else can see it. Don’t feel the need to explain your colostomy to everyone who asks. Only share as much as you want to.

For some people and their immediate family members, a colostomy can cause depression, anxiety, or self-esteem issues. Ask for mental health resources if you or your immediate family is having a hard time adjusting to the surgery. A short explanation would simply be that you had abdominal surgery. Think about joining a support group to help adjust to the colostomy. Your ostomy nurse or healthcare team can provide support group resources.