Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

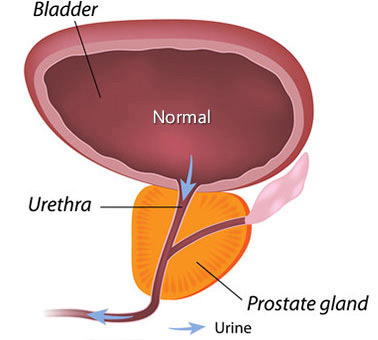

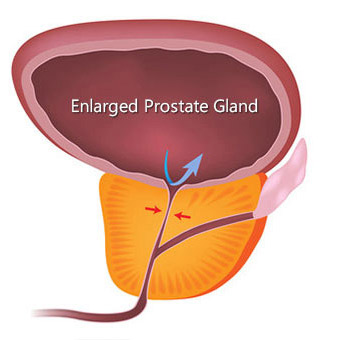

Benign prostatic hyperplasia, a noncancerous enlargement of the prostate gland, is the most common benign tumor found in men.

As is true for prostate cancer, BPH occurs more often in the West than in Eastern countries, such as Japan and China, and it may be more common among black people. Not long ago, a study found a possible genetic link for BPH in men younger than age 65 who have a very enlarged prostate: Their male relatives were four times more likely than other men to need BPH surgery at some point in their lives, and their brothers had a sixfold increase in risk.

BPH produces symptoms by obstructing the flow of urine through the urethra. Symptoms related to BPH are present in about one in four men by age 55, and in half of 75-year-old men. However, treatment is only necessary if symptoms become bothersome. By age 80, some 20% to 30% of men experience BPH symptoms severe enough to require treatment. Surgery was the only option until the recent approval of minimally invasive procedures that open the prostatic urethra, and drugs that can relieve symptoms either by shrinking the prostate or by relaxing the prostate muscle tissue that constricts the urethra.

Signs and Symptoms

BPH symptoms can be divided into those caused directly by urethral obstruction and those due to secondary changes in the bladder.

Typical obstructive symptoms are:

- Difficulty starting to urinate despite pushing and straining

- A weak stream of urine; several interruptions in the stream

- Dribbling at the end of urination

Bladder changes cause:

- A sudden strong desire to urinate (urgency)

- Frequent urination

- The sensation that the bladder is not empty after urination is completed

- Frequent awakening at night to urinate (nocturia)

As the bladder becomes more sensitive to retained urine, a man may become incontinent (unable to control the bladder, causing bed wetting at night or inability to respond quickly enough to urinary urgency).

Burning or pain during urination can occur if a bladder tumor, infection or stone is present. Blood in the urine (hematuria) may herald BPH, but most men with BPH do not have hematuria.

Screening and Diagnosis

The American Urological Association (AUA) Symptom Index provides an objective assessment of BPH symptoms that helps determine treatment. However, this index cannot be used for diagnosis, since other diseases can cause symptoms similar to those of BPH.

A medical history will give clues regarding conditions that can mimic BPH, such as urethral stricture, bladder cancer or stones, or abnormal bladder/pelvic floor function (problems with holding or emptying urine) due to a neurologic disorder (neurogenic bladder) or pelvic floor muscle spasms. Strictures can result from urethral damage caused by prior trauma, instrumentation (for example, catheter insertion) or an infection such as gonorrhea. Bladder cancer is suspected if there is a history of blood in the urine.

Pain in the penis or bladder area may indicate bladder stones, infections, or irritation or compression of the pudendal nerve. A neurogenic bladder is suggested when a man has diabetes or a neurologic disease such as multiple sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease, or recent deterioration in sexual function. A thorough medical history should include questions about any worsening of urinary symptoms when taking cold or sinus drugs, and previous urinary tract infections or prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate, which may cause pain in the lower back and the area between the scrotum and rectum, and chills, fever and general malaise). The physician will also ask whether any over-the-counter or prescription medications are being taken, because some can make voiding symptoms worse in men with BPH.

The physical examination may begin with the doctor observing urination to completion to detect any urinary irregularities. The doctor will manually examine the lower abdomen to check for a mass, which may indicate an enlarged bladder due to retained urine. In addition, a digital rectal exam (DRE), which allows the physician to assess the prostate’s size, shape and consistency, is essential for proper diagnosis. During this important examination, a gloved finger is inserted into the rectum — this is only mildly uncomfortable. The detection of hard or firm areas in the prostate raises suspicion of prostate cancer. If the history suggests possible neurologic disease, the physical may include an examination for neurologic abnormalities that indicate the urinary symptoms result from a neurogenic bladder.

A urinalysis, which is performed for all patients with symptoms of BPH, may be the only laboratory test if symptoms are mild and no other abnormalities are suspected from the medical history and physical examination. A urine culture is added if a urinary infection is suspected. With more severe, chronic BPH symptoms, blood creatinine of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and hemoglobin are measured to rule out kidney damage and anemia. Measuring prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels in the blood to screen for prostate cancer is recommended, as well as performing the DRE. PSA testing alone cannot determine if symptoms are due to BPH or prostate cancer, because both conditions can elevate PSA levels.

Treatment

When is BPH treatment necessary?

The course of BPH in any individual is not predictable. Symptoms, as well as objective measurements of urethral obstruction, can remain stable for many years and may even improve over time for as many as one-third of men, according to some studies. In a study from the Mayo Clinic, urinary symptoms did not worsen over a 3.5-year period in 73% of men with mild BPH. A progressive decrease in the size and force of the urinary stream and the feeling of incomplete bladder emptying are the symptoms most correlated with the eventual need for treatment. Although nocturia is one of the most annoying BPH symptoms, it does not predict the need for future intervention.

If worsening urethral obstruction is left untreated, possible complications are a thickened, irritable bladder with reduced capacity for urine; infected residual urine or bladder stones; and a backup of pressure that damages the kidneys.

Decisions regarding treatment are based on the severity of symptoms (as assessed by the AUA Symptom Index), the extent of urinary tract damage and the man’s overall health. In general, no treatment is indicated in those who have only a few symptoms and are not bothered by them. Intervention — usually surgical — is required in the following situations:

- Inadequate bladder emptying resulting in damage to the kidneys

- Complete inability to urinate after acute urinary retention

- Incontinence due to overfilling or increased sensitivity of the bladder

- Bladder stones

- Infected residual urine

- Recurrent severe hematuria

- Symptoms that trouble the patient enough to diminish his quality of life

Treatment decisions are more difficult for men with moderate symptoms. They must weigh the potential complications of treatment against the extent of their symptoms. Each individual must determine whether the symptoms interfere with his life enough to merit treatment. When selecting a treatment, both patient and doctor must balance the effectiveness of different forms of therapy against their side effects and costs.

Treatment Options for BPH

Currently, the main options to address BPH are:

- Watchful waiting

- Medication

- Surgery (prostatic urethral lift, transurethral resection of the prostate, photovaporization of the prostate, open prostatectomy)

If medications are ineffective in a man who is unable to withstand the rigors of surgery, urethral obstruction and incontinence may be managed by intermittent catheterization or an indwelling Foley catheter (which has an inflated balloon at the end to hold it in place in the bladder). The catheter can remain indefinitely (it is usually changed monthly).

Watchful Waiting

Because the progress and complications of BPH are unpredictable, a strategy of watchful waiting — no immediate treatment is attempted — is best for those with minimal symptoms that are not especially bothersome. Physician visits are needed about once per year to review the progress of symptoms, perform an examination and do a few simple laboratory tests. During watchful waiting, the man should avoid tranquilizers and over-the-counter cold and sinus remedies that contain decongestants. These drugs can worsen obstructive symptoms. Avoiding fluids at night may lessen nocturia.

Medication

Data is still being gathered on the benefits and possible adverse effects of long-term medical therapy. Currently, two types of drugs — 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors and alpha-adrenergic blockers — are used to treat BPH. Preliminary research suggests that these drugs improve symptoms in 30% to 60% of men, but it is not yet possible to predict who will respond to medical therapy or which drug will be better for an individual patient.

5-Alpha-Reductase Inhibitors

Finasteride (Proscar) blocks the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, the major male sex hormone found in cells of the prostate. In some men, finasteride can relieve BPH symptoms, increase urinary flow rate and shrink the prostate, though it must be used indefinitely to prevent recurrence of symptoms, and it may take as long as six months to achieve maximum benefits.

In a study of its safety and effectiveness, two-thirds of the men taking finasteride experienced:

- At least a 20% decrease in prostate size (only about half achieved this level of reduction by the one-year mark)

- Improved urinary flow for about one-third of patients

- Some relief of symptoms for two-thirds of patients

A study published last year suggests that finasteride may be best suited for men with relatively large prostate glands. An analysis of six studies found that finasteride only improved BPH symptoms in men with an initial prostate volume of over 40 cubic centimeters — finasteride did not reduce symptoms in men with smaller glands. Since finasteride shrinks the prostate, men with smaller glands are probably less likely to respond to the drug because the urinary symptoms result from causes other than physical obstruction (for example, smooth muscle constriction). A recent study showed that over a four-year period of observation, finasteride treatment reduced the risk of developing urinary retention or requiring surgical treatment by 50%.

Finasteride use comes with some side effects. Impotence occurs in 3% to 4% of men taking the drug, and patients experience a 15% reduction in their sexual function scores regardless of their age and prostate size. Finasteride may also decrease the volume of ejaculate. Another adverse effect is gynecomastia (breast enlargement). A study from England found gynecomastia in 0.4% of patients taking the drug. About 80% of those who stop taking it have a partial or full remission of their breast enlargement. Because it is not clear that the drug causes gynecomastia or that it increases the risk of breast cancer, men taking finasteride are being carefully monitored until these issues are resolved. Men exposed to finasteride or dutasteride are also at risk of developing post-finasteride syndrome, which is characterized by a constellation of symptoms, including some that are sexual (reduced libido, ejaculatory dysfunction, erectile dysfunction), physical (gynecomastia, muscle weakness) and psychological (depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts). These symptoms can persist long term despite discontinuation of finasteride.

Finasteride can lower PSA levels by about 50%, but it is not thought to limit the utility of PSA as a screening test for prostate cancer. The fall in PSA levels, and any adverse effects on sexual function, disappear when finasteride use is stopped.

To obtain the benefits of finasteride for BPH without compromising the detection of early prostate cancer, men should have a PSA test before starting finasteride treatment. Subsequent PSA values can then be compared to this baseline value. If a man is already on finasteride and no baseline PSA level was obtained, the results of a current PSA test should be multiplied by two to estimate the true PSA level. A fall in PSA of less than 50% after a year of finasteride treatment suggests either that the drug is not being taken or that prostate cancer might be present. Any increase in PSA levels while taking finasteride also raises the possibility of prostate cancer.

Alpha-Adrenergic Blockers

These drugs, originally used to treat high blood pressure, reduce the tension of smooth muscles in blood vessel walls and relax smooth muscle tissue in the prostate. As a result, daily use of an alpha-adrenergic drug may increase urinary flow and relieve symptoms of urinary frequency and nocturia. Some alpha-l-adrenergic drugs — for example, doxazosin (Cardura), prazosin (Minipress), terazosin (Hytrin) and tamsulosin (selective alpha 1-A receptor blocker — Flomax) — have been used for this purpose. One recent study found that 10 milligrams (mg) of terazosin daily produced a 30% reduction of BPH symptoms in about two-thirds of the men taking the drug. Lower daily doses of terazosin (2 and 5 mg) did not produce as much benefit as the 10 mg dose. The report’s authors recommended that physicians gradually increase the dose to 10 mg unless troublesome side effects occur. Possible side effects of alpha-adrenergic blockers are orthostatic hypotension (dizziness upon standing, due to a fall in blood pressure), fatigue and headaches. In this study, orthostatic hypotension was the most frequent side effect, and the authors noted that taking the daily dose in the evening can mitigate the problem. Another troubling side effect of alpha-blockers is the development of ejaculatory dysfunction (up to 16% of patients will experience this). In a study of over 2,000 BPH patients, a maximum of 10 mg of terazosin reduced average AUA Symptom Index scores from 20 to 12.4 over one year, compared to a drop from 20 to 16.3 in patients taking a placebo.

An advantage of alpha blockers, compared to finasteride, is that they work almost immediately. They also have the additional benefit of treating hypertension when it is present in BPH patients. However, whether terazosin is superior to finasteride may depend more on the prostate’s size. When the two drugs were compared in a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine, terazosin appeared to produce greater improvement of BPH symptoms and urinary flow rate than finasteride. But this difference may have been due to the larger number of men in the study with small prostates, who would be more likely to have BPH symptoms from smooth muscle constriction rather than from physical obstruction by excess glandular tissue. Doxazosin was evaluated in three clinical studies of 337 men with BPH. Patients took either a placebo or 4 mg to 12 mg of doxazosin per day. The active drug reduced urinary symptoms by 40% more than the placebo, and it increased urinary peak flow by an average of 2.2 ml/s (compared to 0.9 ml/s for the placebo patients).

Despite the previously held belief that doxazosin was only effective for mild or moderate BPH, patients with severe symptoms experienced the greatest improvement. Side effects including dizziness, fatigue, hypotension (low blood pressure), headache and insomnia led to withdrawal from the study by 10% of those on the active drug and 4% of those taking the placebo. Among men treated for hypertension, the doses of anti-hypertension drugs may need to be adjusted due to the blood-pressure-lowering effects of an alpha-adrenergic blocker.

Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibitors

Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, such as Cialis, are commonly used for erectile dysfunction, but when used daily, they also can relax the smooth muscle of the prostate and overactivity of the bladder muscle. Studies examining the impact of daily Cialis use compared to placebo demonstrated a reduction in International Prostate Symptom Score by four to five points, and Cialis was superior to placebo in reducing urinary frequency, urgency and urinary incontinence episodes. Studies examining Cialis’ impact on urine flow, however, have not shown meaningful change.

Surgery

Surgical treatment of the prostate involves displacement or removal of the obstructing adenoma of the prostate. Surgical therapies have historically been reserved for men who failed medical therapy and those who developed urinary retention secondary to BPH, recurrent urinary tract infections, bladder stones or bleeding from the prostate. However, a large number of men are poorly compliant with medical therapy due to side effects. Surgical therapy can be considered for these men to prevent long-term deterioration of bladder function.

Current surgical options include monopolar and bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), robotic simple prostatectomy (retropubic, suprapubic and laparoscopic), transurethral incision of the prostate, bipolar transurethral vaporization of the prostate (TUVP), photoselective vaporization of the prostate (PVP), prostatic urethral lift (PUL), thermal ablation using transurethral microwave therapy (TUMT), water vapor thermal therapy, transurethral needle ablation (TUNA) of the prostate and enucleation using holmium (HoLEP) or thulium (ThuLEP) laser.

Thermal Treatments

Thermal procedures alleviate symptoms by using convective heat transfer from a radiofrequency generator. Transurethral needle ablation (TUNA) of the prostate uses low-energy radio waves, delivered by tiny needles at the tip of a catheter, to heat prostatic tissue. A six-month study of 12 men with BPH (age 56 to 76) found the treatment reduced AUA Symptom Index scores by 61%, and produced minor side effects (including mild pain or difficulty urinating for one to seven days in all the men). Retrograde ejaculation occurred in one patient. Another thermal treatment, transurethral microwave therapy (TUMT), is a minimally invasive alternative to surgery for patients with bladder outflow obstruction caused by BPH. Performed on an outpatient basis under local anesthesia, TUMT damages prostatic tissue by microwave energy (heat) that is emitted from a urethral catheter.

A new form of thermal therapy, called water vapor thermal therapy or Rezum, involves conversion of thermal energy into water vapor to cause cell death in the prostate. Studies examining the six-month prostate size after water vapor thermal therapy demonstrated a 29% reduction in prostate size by MRI.

With thermal therapies, several treatment sessions may be necessary, and most men need more treatment for BPH symptoms within five years after their initial thermal treatment.

Transurethral Incision of the Prostate (TUIP)

This procedure was first used in the U.S. in the early 1970s. Like transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), it is done with an instrument that is passed through the urethra. But instead of removing excess tissue, the surgeon only makes one or two small cuts in the prostate with an electrical knife or laser, relieving pressure on the urethra. TUIP can only be done for men with smaller prostates. It takes less time than TURP, and it can be performed on an outpatient basis under local anesthesia in most cases. A lower incidence of retrograde ejaculation is one of its advantages.

Prostatic Urethral Lift (UroLift)

In contrast to the other therapies that ablate or resect prostate tissue, the prostatic urethral lift procedure involves placing UroLift implants into the prostate under direct visualization to compress the prostate lobes and unobstruct the prostatic urethra. The implants are placed using a needle that passes through the prostate to deliver a small metallic tab anchoring it to the prostate capsule. Once the capsular tab is placed, a suture connected to the capsular tab is tensioned and a second stainless steel tab is placed on the suture to lock it into place. The suture is severed.

Transurethral Prostatectomy (TURP)

This procedure is considered the “gold standard” of BPH treatment — the one against which other therapeutic measures are compared. It involves removal of the core of the prostate with a resectoscope — an instrument passed through the urethra into the bladder. A wire attached to the resectoscope removes prostate tissue and seals blood vessels with an electric current. A catheter remains in place for one to three days, and a hospital stay of one or two days is generally required. TURP causes little or no pain, and full recovery can be expected by three weeks after surgery. In carefully selected cases (patients with medical problems and smaller prostates), TURP may be possible as an outpatient procedure.

Improvement after surgery is greatest in those with the worst symptoms. Marked improvement occurs in about 93% of men with severe symptoms and in about 80% of those with moderate symptoms. The mortality from TURP is very low (0.1%). However, impotence follows TURP in about 5% to 10% of men, and incontinence occurs in 2% to 4%.

Prostatectomy

Prostatectomy is a very common operation. About 200,000 of these procedures are carried out annually in the U.S. A prostatectomy for benign disease (BPH) involves removal of only the inner portion of the prostate (simple prostatectomy). This operation differs from a radical prostatectomy for cancer, in which all prostate tissue is removed. Simple prostatectomy offers the best and fastest chance to improve BPH symptoms, but it may not totally alleviate discomfort. For example, surgery may relieve the obstruction, but symptoms may persist due to bladder abnormalities.

Surgery causes the greatest number of long-term complications, including:

- Impotence

- Incontinence

- Retrograde ejaculation (ejaculation of semen into the bladder rather than through the penis)

- The need for a second operation (in 10% of patients after five years) due to continued prostate growth or a urethra stricture resulting from surgery

While retrograde ejaculation carries no risk, it may cause infertility and anxiety. The frequency of these complications depends on the type of surgery.

Surgery is delayed until any urinary tract infection is successfully treated and kidney function is stabilized (if urinary retention has resulted in kidney damage). Men taking aspirin should stop seven to 10 days before surgery, since aspirin interferes with blood’s ability to clot.

Transfusions are required in about 6% of patients after TURP and 15% of patients after open prostatectomy.

Since the timing of prostate surgery is elective, men who may need a transfusion — primarily those with a very large prostate, who are more likely to experience significant blood loss — have the option of donating their own blood in advance, in case they need it during or after surgery. This option is referred to as an autologous blood transfusion.

Open Prostatectomy

An open prostatectomy is the operation of choice when the prostate is very large — e.g., >80 grams (since transurethral surgery cannot be performed safely in these men). However, it carries a greater risk of life-threatening complications in men with serious cardiovascular disease, because the surgery is more extensive than TURP or TUIP.

In the past, open prostatectomies for BPH were carried out either through the perineum — the area between the scrotum and the rectum (the procedure is called perineal prostatectomy) — or through a lower abdominal incision. Perineal prostatectomy has largely been abandoned as a treatment for BPH due to the higher risk of injury to surrounding organs, but it is still used for prostate cancer. Two types of open prostatectomy for BPH — suprapubic and retropubic — employ an incision extending from below the umbilicus (navel) to the pubis. A suprapubic prostatectomy involves opening the bladder and removing the enlarged prostatic nodules through the bladder. In a retropubic prostatectomy, the bladder is pushed upward and the prostate tissue is removed without entering the bladder. In both types of operation, one catheter is placed in the bladder through the urethra, and another through an opening made in the lower abdominal wall. The catheters remain in place for three to seven days after surgery. The most common immediate postoperative complications are excessive bleeding and wound infection (usually superficial). Potential complications that are more serious include heart attack, pneumonia and pulmonary embolus (blood clot in the lungs). Breathing exercises, leg movements in bed and early ambulation are aimed at preventing these complications. The recovery period and hospital stay are longer than for transurethral prostate surgery.