Achalasia

Achalasia, a rare swallowing disorder, is a lifelong condition that may have serious symptoms. With proper treatment, symptoms can be managed so they do not disrupt everyday life.

What You Need to Know

- Achalasia, also known as esophageal achalasia or achalasia cardia, is a rare swallowing disorder affecting about eight to 12 people per 100,000.

- People with achalasia have trouble with the muscles in the esophagus, which do not work well to move swallowed food into the stomach.

- Achalasia symptoms can include difficulty swallowing and food “sticking” in the esophagus, regurgitation (food coming back up), weight loss, chest pain and cough.

- Treatments aim to make it easier for the food to pass from the esophagus into the stomach by loosening the muscles involved in this process.

What is achalasia?

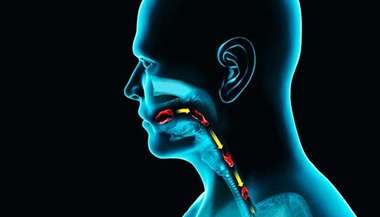

Achalasia is a rare swallowing disorder that affects the esophagus (the tube between the throat and the stomach). In people with achalasia, the esophagus muscles do not contract properly and do not help propel food down toward the stomach. At the same time, the ring of muscle at the bottom end of the esophagus, called the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), is unable to relax to let the food into the stomach.

Achalasia typically affects adults between 30 and 60 years of age, with a peak in the 40s. The disorder is about twice as common in men than women.

Achalasia Causes

The causes of achalasia are unknown, but researchers are exploring several theories. One is related to degeneration of the nerve cells located between the layers of esophageal muscles. These nerve cells enable the esophagus to push food toward and into the stomach.

Some studies suggest a possible relationship between achalasia and parasitic or viral infections. People with achalasia may be more likely to show evidence of previous infections, such as antibodies to the herpes simplex virus, human papillomavirus, measles virus and others.

There is also evidence that achalasia may be an inflammatory autoimmune disorder, which means it could be caused by the body attacking itself. Researchers have seen signs of immune system activity in the nerve cells that empower esophageal muscles. Also, patients with achalasia are 3.6 times more likely to have an autoimmune disorder such as uveitis, type I diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome.

Achalasia Symptoms

Some achalasia symptoms are caused by food piling up in the esophagus and being unable to pass into the stomach. As the esophagus fills up, it widens and can become twisted. Other achalasia symptoms are related to the abnormal contractions of the esophageal muscles.

Symptoms of achalasia occur during or after eating. They include:

- The feeling that food or liquid are hard to swallow and are getting caught in the esophagus or “sticking” on the way down to the stomach (this is the most common symptom of achalasia)

- Regurgitation (food and liquid backing up into the mouth after being swallowed)

- Chest pain, which can be severe and awaken the person from sleep

- Heartburn

- Coughing, especially at night

- Choking,or inhalation of food or liquid into the airways (aspiration)

Both chest pain and regurgitation, some of the first symptoms a person with achalasia might experience, are also associated with gastroesophageal reflux disorder (GERD). However, the two conditions are different. GERD is caused by a lower esophageal sphincter that is too loose, allowing stomach acid to enter the esophagus. With achalasia, the sphincter is too tight.

Achalasia symptoms can become serious. Severe achalasia may lead to significant chest pain, fatigue, malnutrition and weight loss. If food particles enter the airways due to coughing and choking while eating, it can lead to pneumonia — inflammation in the airways that can become life threatening.

Types of Achalasia

The way muscles in the esophagus malfunction in people with achalasia varies. In all cases of achalasia, the lower esophageal sphincter that controls the passage between the esophagus and the stomach fails to relax at the right time. Based on other problems that happen at the same time, doctors identified three types of achalasia:

- Type 1 achalasia is sometimes called classic achalasia. With this type, the esophagus muscles barely contract, so food moves down because of gravity alone.

- In Type 2 achalasia, pressure builds up in the esophagus, causing it to become compressed. This is the most common type of achalasia and it often causes more severe symptoms than type I.

- Type III achalasia is sometimes called spastic achalasia because there are abnormal contractions at the bottom of the esophagus where it meets the stomach. This is the most severe type of achalasia. The contractions can cause chest pain that can awaken a person from sleep and imitate the symptoms of a heart attack.

Achalasia Diagnosis

In addition to a thorough physical examination and review of your medical history and symptoms, your doctor may recommend the following tests to help diagnose achalasia.

- Pharyngeal and esophageal manometry to measure and record changes in pressure throughout the throat and esophagus as you swallow. Some consider manometry to be the most reliable test for achalasia, since it can detect the location and severity (or lack of) muscle contractions that affect the ability to swallow.

- Upper endoscopy to examine the esophagus and stomach using an endoscope — a thin tube with a camera that is inserted through the mouth. This test helps see abnormalities in the esophagus such as strictures (narrowing) and tumors. During endoscopy, your doctor can perform a biopsy or remove abnormal tissue for further analysis.

- Wireless pH testing or 24-hour pH impedance testing to evaluate the acidity in the esophagus during an extended period and rule out other conditions such as GERD.

- Barium swallow, an imaging test that uses the contrast medium barium and X-rays to create images of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This test may reveal a dramatic narrowing of the esophagus, which is sometimes called an achalasia bird beak.

Achalasia Treatment

Currently, no treatments resolve achalasia entirely, but there are several approaches to relieve symptoms, such as dilation, surgery, botulinum toxin injections and medications. The goal of treatment is to normalize contractions in the esophagus and help the sphincter relax and allow food to pass into the stomach.

Dilation of the Esophageal Sphincter

Dilation of a passageway means widening it. During a dilation procedure for achalasia, the patient is asleep while a gastroenterologist inserts an endoscope into the mouth and esophagus, and slowly inflates a balloon near the lower esophageal sphincter. This can decrease the pressure in the esophagus and stretch the sphincter muscles until they relax enough to allow food and liquid to pass through easily.

Balloon dilation is probably the most common approach to treating achalasia. Most patients (65% to 80%) report a significant improvement of swallowing after the procedure. However, the improvement may be temporary — achalasia symptoms can return over time, calling for further treatment.

Achalasia Surgery — Esophageal Myotomy

During myotomy, a gastroenterologist cuts the muscles in the esophagus, esophageal sphincter and lower stomach to prevent them from tightening.

An achalasia myotomy can be performed through the mouth with an endoscope (peroral endoscopic myotomy or POEM) or through several small incisions in the abdomen (laparoscopic Heller myotomy). A lower esophageal sphincter myotomy disrupts just enough muscle to relieve achalasia symptoms but not enough to cause acid reflux. This is the most permanent solution for achalasia, but it is not appropriate for all patients.

Cutting Edge Treatment for Achalasia — POEM Procedure

Botulinum Toxin Injections

Injecting botulinum toxin into the lower esophageal sphincter has been shown to help some patients who have achalasia. These treatments are particularly useful for older patients and those who are not candidates for dilation or myotomy.

Botulinum toxin injections for achalasia work by numbing the sphincter and surrounding nerves, allowing it to relax. The injections are done with a special needle inserted through an endoscope. They have a limited effect, which lasts about one year. Repeating injections may be necessary. Some patients may experience mild chest pain, and there have been reports of skin rashes after this treatment.

Medications for Achalasia

Medications are generally not effective in treating achalasia. Some drugs containing nitrates or calcium channel blockers can help temporarily relax the lower esophageal sphincter. However, they must be taken before every meal, and their side effects usually outweigh the benefits.

Living with Achalasia

If you continue to have symptoms after achalasia treatment, you should work with your doctor to explore other solutions. Modifying your diet, eating habits or other lifestyle factors could play a role in your quality of life.

Is there an achalasia diet?

No diet is proved to help with achalasia symptoms, but you should discuss with your doctor or a speech-language pathologist if you should change what you eat. Certain foods can be harder or less difficult to swallow depending on the type of achalasia you have. Also, if you have lost much weight because of achalasia, your doctor may recommend high calorie foods to make sure you have a healthy body mass index.

Some people with achalasia feel better when avoiding certain foods, such as:

- Raw fruits and vegetables

- Tough cuts of meat

- Highly acidic foods such as citrus fruits

- Alcohol

- Caffeine

How and when you eat can make a difference too. Small bites of food, chewed carefully, can be easier to swallow. Avoiding solid foods before bedtime can minimize nighttime chest pain and regurgitation.

Is achalasia deadly?

People don’t typically die because of achalasia. Although it tends to be a lifelong condition, with symptom management, you can avoid the most serious complications of achalasia, such as aspiration, choking and malnutrition.

People with achalasia tend to have a higher risk of developing esophageal cancer. Discuss with your doctor if you have family history of this type of cancer or other factors that may further increase your risk.