Kidney Cancer Study Uncovers New Subtypes and Clues to Better Diagnosis and Treatment

10/31/2019

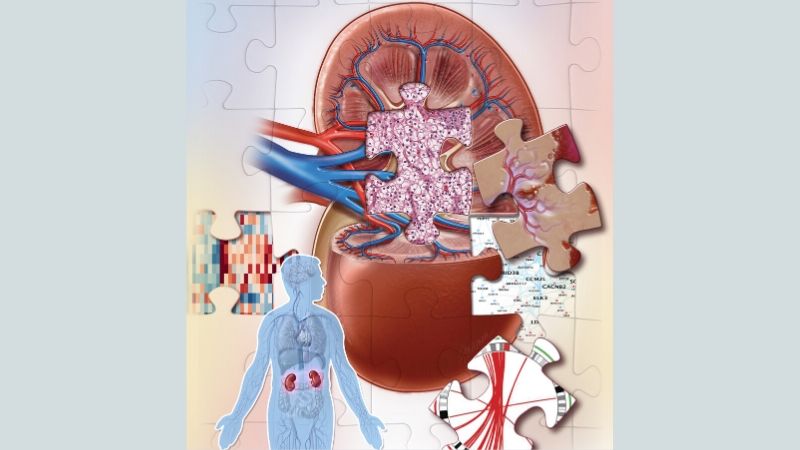

In what is believed to be the most comprehensive molecular characterization to date of the most common — and often treatment-resistant — form of kidney cancer, researchers at Johns Hopkins’ departments of pathology and oncology, Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine report evidence for at least three distinct subtypes of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), along with new revelations about the proteins that define them. Their findings could inform overall patient survival and response to treatment.

Their deep dive investigation of ccRCC, described in the Oct. 31 issue of the journal Cell, involved tumor samples from 110 patients who had not yet received treatment, such as chemotherapy and radiation, and 84 samples of healthy tissue surrounding the tumors.

The researchers used the most advanced genomic and proteomic technologies available to tease out their proteogenomic characteristics, defined as genetic makeup (genomics), chemical modifications to DNA (epigenomics), messenger RNA located in cells that serves as template to make proteins (transcriptomics), and proteins (proteomics) and their modification by phosphate group (phosphoproteomics), a modification known to regulate protein functions by switching on or off. The work was completed as part of the National Cancer Institute’s Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC), a national effort to better understand cancers through proteogenomics.

Among their findings, investigators say, was that the loss of chromosome 3p is an apparent hallmark of ccRCC, occurring in almost all of the tumor samples in the study.

In addition, the researchers identified four distinct immune-based subtypes of ccRCC based on their immune cell differences that potentially could be used to help predict patients’ overall survival and response to treatment.

Among all kidney cancers, ccRCC accounts for 75%, equating to about 65,000 new cases annually. Surgical removal remains the only effective treatment for cancers that have not spread beyond the kidney, but 30% of patients present with advanced disease at diagnosis.

“Historically, ccRCC has been considered resistant to conventional chemotherapy and radiation, and response to several FDA-approved drugs has been limited,” says Daniel W. Chan, Ph.D., a professor of pathology and oncology, and director of the Center for Biomarker Discovery and Translation at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “The National Cancer Institute’s The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) has catalogued genetic alterations responsible for many cancers including ccRCC, but questions remained.”

“Our results illustrate the complexity of cancer development, and that we can use proteomics and phosphoproteomics in addition to genomics to learn more about cancer phenotypes and their heterogeneity,” says Hui Zhang, Ph.D., co-principal investigator of the study, professor of pathology and oncology, and director of the Mass Spectrometry Core Facility at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“The use of one type of molecular study to understand cancer is no longer enough. A multi-omic approach is needed to fully characterize cancer,” says lead study author and postdoctoral fellow David J. Clark, Ph.D.

Currently, Clark adds, frontline treatment for ccRCC that cannot be cured surgically is focused on inhibiting angiogenesis, the process by which cancers develop new blood vessels to maintain nourishment and growth, and targeting a protein kinase called mTOR that helps control cell survival and division. Overlaying the proteomic and phosphoproteomic data makes it possible, he says, for researchers to detect a wider array of potential targets for new drug development.

Other key findings of the analysis found that:

There were four distinct subtypes of ccRCC based on their tumor microenvironment signatures:

- CD8-positive inflamed tumors had a high amount of CD8-positive immune cells and responded to cell signaling pathways associated with an immune response.

- CD8-negative inflamed tumors had a near absence of CD8-positive immune cells but did have cells such as fibroblasts, which promote wound healing, and macrophages, which fight cancers and other foreign substances.

- Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) immune desert tumors had no immune cells but had a strong presence of endothelial cells associated with the development of new blood vessel growth in tumor progression.

- Metabolic immune desert cells were more pure tumor cells with almost no immune cells and very few fibroblasts.

Based on The Cancer Genome Atlas data, Clark says, it appeared that those with CD8-positive inflamed tumors would have a worse overall survival while those with VEGF immune desert tumors would have the best overall survival. New predictive models by the researchers found that those with CD8-positive tumors would have the best response to immune checkpoint therapies, whereas those with VEGF immune desert tumors would show the best response to anti-angiogenesis therapies, targeted treatments that cut tumors off from their blood supply.

“Overall, this study reveals unique biological insights that are gained only when combining complementary proteomic and genomic analyses,” says Zhang. “Our multi-level omics analysis identified underlying molecular mechanisms that are not fully captured at the genomic level, and defines protein phosphorylation and immune signatures necessary to stratify ccRCC patients with the goal of developing better, more targeted therapeutic interventions.”

The team next plans to use similar methods to more fully characterize pancreatic and head and neck cancers.

Other study co-authors include Jianbo Pan, Yingwei Hu, Tung-Shing M. Lih, Lijun Chen, Qing Kay Li, Michael Schnaubelt, Minghui Ao, Kyung-Cho Cho, Shiyong Ma, Philip M. Pierorazio, Christian P. Pavlovich, Jiang Qian and Zhen Zhang of Johns Hopkins. Other investigators contributing to the study were from the University of Michigan; the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York; Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md.; Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis; the University of Chicago; MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston; the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine; New York University School of Medicine; Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.; Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York; Poznań University of Medical Sciences, Poland; Pomeranian University of Medicine, Poland; the International Institute for Molecular Oncology, Poland; Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, Md.; and Sema4, Stamford, Conn.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute’s Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) grant U24CA210985.