Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH)

What is congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH)?

The diaphragm is a thin sheet of muscle that separates the chest from the abdominal cavity. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) occurs when there is an opening in the diaphragm which allows the bowel, stomach, and liver to move upward into the chest cavity as the fetus develops. The presence of abdominal organs in the chest limits the space for the lungs to develop normally and can lead to breathing complications after the baby is born. At birth, the lungs are smaller than expected (pulmonary hypoplasia) so nearly all newborns with CDH have breathing problems that can be life threatening.

CDH occurs in about 1 in 3,000 live births and most frequently occurs on the left side only. In one third of babies with diaphragmatic hernia, there are also defects in the development of the heart or other organs.

The two types of diaphragmatic hernia are:

Bochdalek hernia. By far the most common type, this involves the side and back of the diaphragm. The stomach, liver, spleen or intestines move up into your baby’s chest cavity.

Morgagni hernia. This type involves the front part of the diaphragm, is rarely detected before birth and does not lead to severe breathing problems.

All babies born with CDH need specialized care as soon as the diagnosis is made. Most parents learn at the prenatal sonogram around 20 weeks’ gestation that their fetus has CDH. Prenatal CDH diagnosis offers parents the benefit to gain important information about the details of the CDH. Most parents transfer their care to maternal-fetal medicine providers trained to manage high-risk pregnancies and meet pediatric providers that are experts in the specialized care required for babies with CDH after birth. Since some CDH cases are much more severe than others, these consultations give parents the option to deliver at a hospital best equipped for the care needs of the baby and family. Some fetuses may be candidates for fetal therapy, which has been shown to improve outcomes in selected cases. Some parents may also choose to explore the option for pregnancy termination.

What causes CDH?

In a normally developing embryo the diaphragm is completely formed by 10 weeks of gestation. In CDH, the process that leads to formation of the diaphragm is disrupted. In 10-15% of CDH cases, the cause is due to a problem with a baby’s chromosomes or by a genetic disorder. In most cases, CDH occurs without an identifiable genetic cause. When there are additional physical abnormalities or a genetic disorder, this is called non-isolated or “complex” CDH. In contrast, when the condition occurs by itself it is called isolated CDH.

Once there is a hole present in the diaphragm, abdominal contents can move into the chest. This is called herniation. Because fetal activity and breathing movements become more frequent and vigorous as a pregnancy continues, the amount of herniation can fluctuate or increase.

When CDH is identified before birth, the goal is to determine the severity of the condition and the next course of action desired by the parents.

What are the potential consequences of CDH?

An important potential consequence of a CDH is underdevelopment of the lungs and their blood vessels known as pulmonary hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension, respectively. Healthy lungs have millions of small air sacs (alveoli) that help the body exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide. In pulmonary hypoplasia, there are fewer air sacs than normal. In pulmonary hypertension, the vessels in the lungs are thicker and resist blood from entering the lungs. There are also fewer blood vessels to receive oxygen since there are fewer alveoli.

Before birth, the placenta provides all functions of the lungs so a fetus can grow in the womb without risk of low oxygen levels. However, after birth, the baby’s lungs take over the function to provide oxygen. In most babies with CDH, a breathing tube is placed at birth and the lungs are supported by a mechanical ventilator. In the most severe cases of CDH, special machines that function as an artificial lung [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)] may be required to support a baby with low oxygen levels despite use of the mechanical ventilator.

How is a congenital diaphragmatic hernia diagnosed?

CDH is most frequently diagnosed during the 20-week prenatal ultrasound. If there is a small hernia, the diagnosis may be made at birth by X-ray when the baby has breathing trouble after birth.

When CDH is diagnosed during pregnancy, most cases are further evaluated with a detailed ultrasound, fetal magnetic resonance imaging and fetal echocardiogram. Genetic counseling is offered. This will help determine the following:

- The side of the hernia and organs that have herniated into the chest.

- If the heart or other organs are not formed normally.

- If the fetus is likely to have a genetic condition.

- The size of the fetal lung in comparison to what would be considered normal.

This information can be gathered by 22 weeks gestation and allow the parents to understand the severity of the CDH. A small percentage of fetuses with CDH also have major chromosomal defects, major heart defects, or CDH on both sides. These patients are more likely to have a poor prognosis.

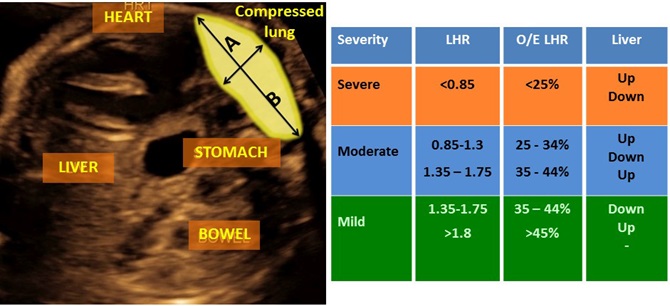

When CDH is isolated, the severity depends on the position of the liver and size of the lungs. In severe CDH, there is a substantial portion of the liver located in the chest and the lungs are very small. Measuring the lung size on the opposite side of the hernia and comparing it to the lung size that is expected for a normal fetus at the same gestational age is the most common approach for evaluating lung size. This measurement is called the observed to expected lung to head ratio (o/e LHR) or lung volume. Based on these measurements by ultrasound, the severity of CDH is determined:

- a lung size less than 25% than expected is considered severe

- a lung size of 35-45% is considered as moderate

- a lung size of greater than 45% is considered mild

For left CDH, the severity of the hernia strongly predicts pulmonary hypoplasia, pulmonary hypertension the need for ECMO, the size of the hernia, survival chance after birth, and long-term complications.

Diaphragmatic Hernia Management and Treatment

Prenatal Care and Delivery Planning

Some fetuses with CDH are at risk for growth delay or increase in the amniotic fluid volume, which can trigger preterm labor. The ultrasound surveillance by the maternal-fetal medicine experts has the goal to manage such complications if they arise. Severe isolated CDH may be eligible for fetal therapy to enhance prenatal lung growth and to improve outcomes after birth.

Fetal Treatment for CDH (Fetoscopic Tracheal Occlusion)

For fetuses with severe CDH, a procedure called fetoscopic tracheal occlusion (FETO), may be an option to increase lung development prior to birth. In this procedure, a miniature telescope (fetoscope) is inserted into the amniotic cavity under anesthesia. The fetal mouth is entered, and a tiny balloon is left inside the windpipe (trachea) for 4-6 weeks. During this time, the balloon prevents any secreted lung liquid from leaving the fetal lungs so lung airway pressure increases. This increased airway pressure results in accelerated lung growth and maturation. The balloon needs to be removed at a second procedure prior to delivery.

Mothers undergoing FETO will need fetal monitoring throughout pregnancy as well as coordinated care with a fetal therapy team and a pediatric surgery and/or neonatology team after birth. Studies have shown that fetuses with severe CDH have higher than expected survival. The benefits of FETO are greatest for centers where the fetal therapy and pediatric teams work in close collaboration.

Postnatal Care

Initial Stabilization

When the baby is born, a breathing tube is placed and a team of expert neonatologists will initiate care using a mechanical ventilator.

Your baby’s health care provider will do an exam and will perform the following tests shortly after birth:

- Chest X-ray – This test will show any issues in your child’s lungs, diaphragm and intestines.

- Arterial blood gas test – This blood test checks how your baby’s lungs are working and how well your baby is breathing.

- Ultrasound of the heart (echocardiogram) – This test shows if your baby has problems with the heart and valves.

In more severe cases, some neonates may need to be placed on ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) since the ventilator may not provide enough support. ECMO, which is only available at specialized centers, is a type of a heart lung machine that puts oxygen in the baby’s blood and removes the carbon dioxide while the lungs rest. Any pulmonary hypertension or heart-related issues are also treated with medications while on ECMO. Most babies who need ECMO remain on this machine for between 1 and 3 weeks. Surgeons can perform the diaphragmatic hernia surgery (if needed) while on the ECMO machine.

Surgery

Once your baby is stable, an operation is performed to move your baby’s abdominal organs out of the chest and to close the hole in the diaphragm. The procedure is performed either through a large abdominal incision or using smaller incisions between the ribs. A synthetic patch is often used to close larger holes in the diaphragm.

After the diaphragm is repaired, most patients can start to receive nutrition (either breast milk or formula) within a week or two after surgery. The amount of support on the mechanical ventilator is slowly reduced until it is safe for the breathing tube to be removed. If a baby does not need ECMO, the average hospital stay is between 3 and 5 weeks. If a baby needs ECMO, the average hospital stay is between 8 and 12 weeks. Most babies will require some medications at discharge to help with lung function and reflux problems associated with feeding.

A Lifeline for the Smallest Patients

NIH-funded research from the lab of pediatric surgeon Shawn Michael Kunisaki helps Johns Hopkins progress the lifesaving repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernias at the Center of Fetal Therapy and Johns Hopkins Children’s Center.

Without research—at Johns Hopkins and at other institutions—scientific breakthroughs suffer, and the lifesaving treatments of tomorrow are at risk.

How can I help my child live with a diaphragmatic hernia?

Babies born with this condition can have long-term health problems. They often need regular follow-up care after they go home from the hospital.

Lung problems

Many babies with more severe CDH will have long-term (chronic) lung problems. Under the supervision of a pediatric pulmonologist, they may need oxygen and medicine to help them breathe. They may need this treatment for weeks, months or years. These problems tend to improve over time as the lungs continue to grow and get stronger. Babies with CDH are more susceptible to colds and other viral illnesses.

Heart problems

Many babies with more severe CDH have pulmonary hypertension that requires medications. Under the supervision of a pediatric cardiologist, this is monitored based on breathing status and echocardiograms. They may need this treatment for weeks, months or years. These problems tend to improve over time as the blood vessels around the lungs continue to mature.

Gastroesophageal reflux

Babies with CDH often have reflux. In this condition, acid and fluids from your baby’s stomach move up into the esophagus. It can cause heartburn, vomiting, lung problems and poor weight gain. Your child’s health care provider may give your child medicine to help. Long-term gastroesophageal reflux is known as gastroesophageal reflux disease or GERD.

Trouble growing

Some babies with more severe CDH will have trouble growing. This is called failure to thrive. Children with serious lung problems are most likely to have growing problems. Because of their illness, they may need more calories than a normal baby to grow and get healthier.

Developmental issues

Babies with this condition may also have developmental problems, especially if ECMO support is needed. They may not roll over, sit, crawl, stand or walk at the same time as healthy babies. These children may need physical, speech and occupational therapy. It can help them gain muscle strength and coordination.

Hearing loss

Some babies may have hearing loss. Your child should have a hearing test before leaving the hospital.

Recurrent diaphragmatic hernia

The diaphragm repair can break apart later in life as babies grow. These children may have a sudden difficulty with breathing or may develop an intestinal blockage. Those at greatest risk of recurrent CDH are those with large hernias requiring a patch repair. The operation to fix recurrent CDH can be more challenging because of scar tissue developed after the first repair. However, most children are stronger and healthier when recurrent CDH is diagnosed so the operation is lower risk.

You’ll work closely with your baby’s health care team. They’ll make a care plan for your baby. Ask your child's health care provider about your child’s outlook.

When should I call my child's health care provider?

Your child’s health care team will tell you how to care for your baby before they leave the hospital. Call your child’s health care provider if your child has new symptoms or if you have questions.

Key points about congenital diaphragmatic hernia

- A diaphragmatic hernia is a birth defect. In this condition, there’s an opening in your baby’s diaphragm. It allows some of the organs that should be found in your child’s belly to move up into the chest cavity.

- The main problem is CDH is the effect of the herniated organs on the developing lungs. The lungs are small and the blood vessels around them do not function very well.

- CDH is most often diagnosed prenatally, which offers the advantage of early establishment of severity and care planning.

- Severe diaphragmatic hernia diagnosed prenatally may benefit from fetal therapy.

- After delivery, babies will need to stay in an intensive care unit. They will need to be put on a breathing machine to help their breathing.

- Once your baby is stabilized, they will need to have surgery to close the diaphragm.

- For some babies CDH can be life-threatening. Survivors often have long-term health issues. They need regular follow-up care after they go home from the hospital.